This study was first published on Asia Times’ Global Risk-Reward Monitor, a weekly economics and geopolitics newsletter. Become a subscriber here.

Gold traded at nearly US$4,300 an ounce for the first time on the afternoon of April 2. We offer here a novel analysis of the gold price, disaggregating its price moves into:

- An industrial metal component

- A hedge against currency depreciation, and

- A geopolitical risk premium

We have noted on several previous occasions that gold diverged from its long-term relationship to TIPS yields on February 2022, that is, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

There is no doubt that a geopolitical risk premium is involved. But how big is it, how has it evolved and what else is affecting gold apart from geopolitical risk?

Among other things, gold is an industrial metal. Industrial applications absorb about 11% of gold demand.

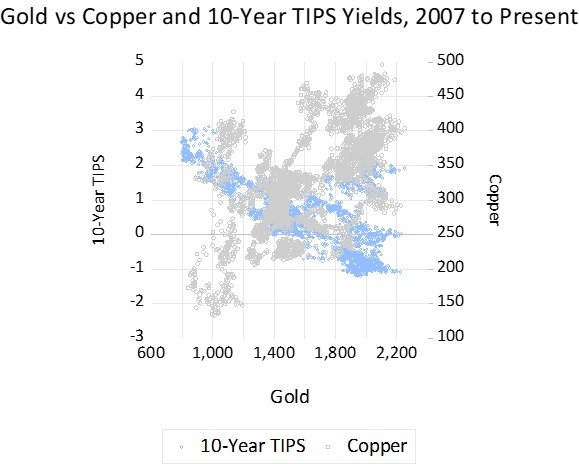

Not surprisingly, there is a robust, significant correlation between the price of gold and that of other industrial metals (the strongest relationship by far is to copper.)

The linear relationship between gold and copper shifts frequently but is still evident in the scatter graph below of post-2007 price relationships.

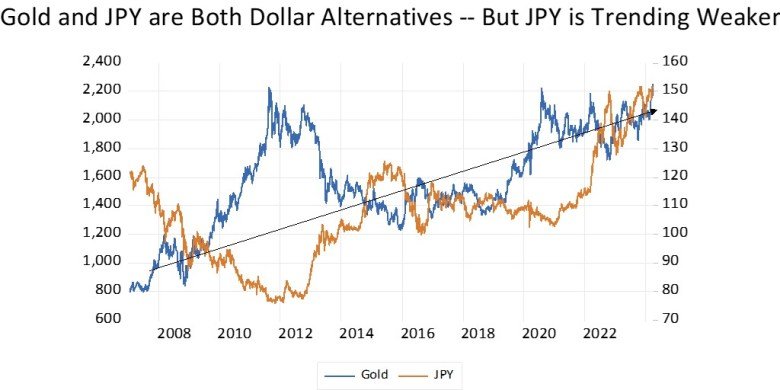

Gold also behaves like a currency, most visibly like the Japanese yen.

There is a clear and consistent inverse relationship between gold and the JPY/USD exchange rate but it shifts steady over time: As JPY depreciated against the US dollar, the gold price rose.

Gold is first of all a hedge against the dollar, that is, against unexpected dollar depreciation and the weakening of alternatives to the dollar adds to demand for gold. We observe a similar but somewhat less consistent relationship between gold and EUR/USD.

The fiscal policies of all the developed countries are in trouble. The United States shows no sign of containing the rapid increase of its national debt.

Japan, whose government debt reached 264% of GDP in 2023, cannot help but continue to monetize its debt, leaving the yen inherently weak.

Germany’s Bundesbank is under pressure to suspend juridical limits to Germany’s debt growth, given the weak economy and funding pressures from the Ukraine war.

That is, all the world’s major developed-market currencies have a long-term structural weakness. That is a positive for gold.

We can obtain a rough idea of the combined impact of TIPS yields, industrial metals and currency weakness on the gold price by regressing the gold price against all three of these factors. By this gauge, the geopolitical risk premium – the residual – is $525, or about 23% of the gold price.

The residual is what is not explained by these three variables and that is as good an estimate of the geopolitical risk premium we can find.

Note that this residual rose noticeably on two previous occasions, namely in 2011, during the European financial crisis of that year, and again after the outbreak of the Covid-19 epidemic.

From this we can infer that geopolitical risk is high and rising, indeed higher than at any time to which this sort of measurement applies.

But there are other reasons for gold to rise, including the lack of fiscal controls in Japan and Europe as well as robust demand for industrial metals. Gold is signaling rising risk but not the end of the world.