So began one of the most inscrutable decisions in Olympics history as the gold went to Devitt, setting off years of protests and appeals by U.S. swimming officials and helping accelerate the introduction of electronic timing to remove the potential variables of human fallibility.

“It was a bad deal,” said Mr. Larson, who died Jan. 19 at age 83 in Orange, Calif.

What happened in Rome remains, even today, a baffling cascade of rulings and questions over judging protocols. In swimming events in those days, the crews who timed races — three people assigned to each lane — were separate from the judges who formally declared the finishing ranks.

Mr. Larson was clocked at 55.0, 55.1 and 55.1 seconds — about a half-second shy of Devitt’s world record. All three timers in Devitt’s lane had him at 55.2.

“Everybody down there told me I had won,” Mr. Larson told reporters after the race. For nearly 10 minutes, the more than 10,000 spectators at Rome’s Stadio Olimpico del Nuoto also believed that Mr. Larson had the gold. Then came signs of discord. The judges who decide the finishing order did not fully agree with the timers.

The three first-place judges had Devitt as winner by a 2-1 vote. But the second-place judges also had Devitt as runner-up, 2-1. The United States and others said the rule book held the solution. In case of such a conflict, they said, the times would decide the winner. Instead, the chief judge at the event, Hans Runströmer of West Germany, stepped in.

Runströmer ordered that Mr. Larson’s time be changed to 55.2, tying with Devitt, then decreed that the Australian had nudged ahead to take the gold. The American coaches were livid. Mr. Larson was in a daze. “I was sick when I learned the race had been given to Devitt,” he said later.

Runströmer was unyielding, saying he had a clear view of who touched the wall first. Photos and video, however, showed Runströmer nearly half a pool length from the lanes assigned to Devitt and Mr. Larson. To stoke further doubts about Runströmer’s claims, the lights at the stadium had been dimmed for dramatic effect during the race, one of the marquee events in Olympic swimming.

To some in the U.S. swimming federation, the decision smacked of anti-American bias even though West Germany was seen as part of the Western camp in the Cold War sports showdowns. Regardless, U.S. officials argued that Runströmer had trampled the rules with his unilateral decision.

The appeals fell flat with the International Olympic Committee and swimming’s international governing body, FINA (now World Aquatics). Runströmer’s ruling stood. As a New York Herald Tribune story noted: “This required a Solomon, and the International Swimming Federation was fresh out of Solomons.”

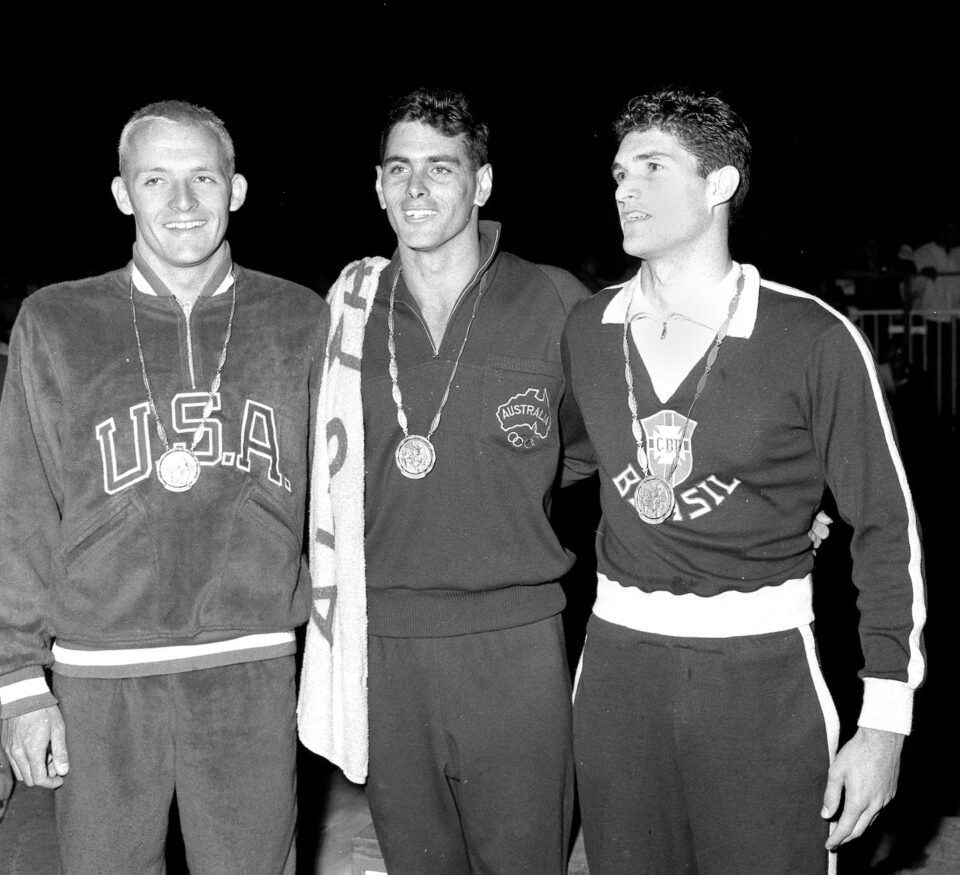

At the medal ceremony, Mr. Larson accepted the silver with a pinched grin. Devitt looked down from the gold medal spot, vigorously applauding Mr. Larson. Brazil’s Manuel dos Santos took third.

“I think,” Mr. Larson told the New York Times, “John [Devitt] has had to live with the feeling for many years that he probably didn’t really win that gold medal.” (Devitt died in August 2023.)

The reverberations from Mr. Larson’s grievance also swept through swimming and the wider reaches of competitive sports.

An experimental — yet unofficial — electronic timing system was used in Rome’s swimming events, clocking Mr. Larson at 55.10 and Devitt at 55.16. Whatever lingering resistance existed over electronic timing began to crumble.

By the 1968 Olympic Games, both winter and summer, electronic timing systems were in wide use, including an insulted touch pad for swimming events developed by Bill Parkinson, a physics professor at the University of Michigan.

Four years later, electronic systems proved decisive in a finish that, to the human eye, was too close to call. At the Munich Games in 1972, Sweden’s Gunnar Larsson took the gold in the 400-meter individual medley by a margin of two-thousandths, 4:31.981 to 4:31.983, over Tim McKee of the United States.

Lance Melvin Larson was born in Monterey Park, Calif., on July 3, 1940. His parents owned a dairy farm and later a gas station, where the young Lance worked. He started swimming to wash away the grime.

In high school, he began breaking swimming records, becoming the first high school swimmer to finish under 50 seconds in the 100-yard freestyle. At the University of Southern California, the 6-foot-1 Mr. Larson was the first in the world to break one minute in the 100-meter butterfly, setting a world record mark two times before the Rome Olympics.

He graduated from USC in 1962 and studied dentistry at the University of the Pacific, getting his degree in 1964. He enlisted in the Navy’s Dental Corps, and left military service in the late 1960s. He later opened a dental practice in Orange, south of Los Angeles.

Mr. Larson’s marriage to Betty Lee Puttler ended in divorce. In 1997, he married the former Sherrie Powell, who confirmed the death but provided no specific cause. Survivors include four sons from his first marriage; two adopted daughters from his second marriage; three stepdaughters; and 10 grandchildren.

Even amid the uproar over the 100-meter freestyle results, Mr. Larson managed to reach the gold medal podium in Rome. He swam the butterfly leg in the 4×100-meter medley relay, where the U.S. team set a new world record of 4:05.4.

After the awards ceremony, Mr. Larson posed for photographers and kissed his gold medal.