Japan’s gold market is undergoing a radical restructuring which has the potential to catapult the Asian nation back to its former place among the world leaders in gold investment, according to Bruce Ikemizu, Chief Director of the Japan Bullion Market Association.

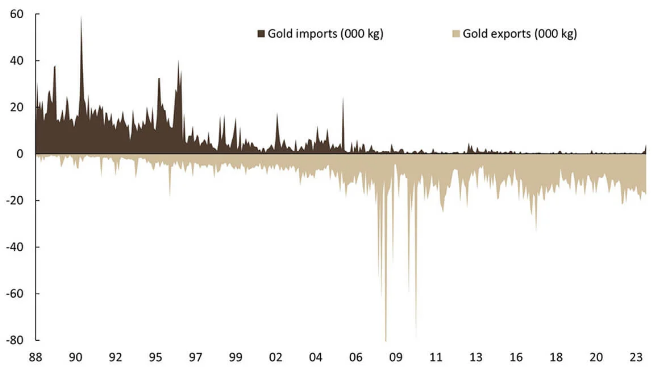

Ikemizu noted that before China became a major player in the global gold market, Japan was one of the world’s largest gold importers. “During the 1980s and 1990s, my primary role in physical gold trading at a trading house involved importing physical gold from Australia, Switzerland, London, South Africa and other sources,” he said. “However, the dynamics of this business gradually shifted after the introduction of a consumption tax, and more dramatically after the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble after the 2000s, following which the country became a net exporter of the gold, marking a 180-degree turn in our business operations.”

The consumption tax was introduced at 3% in 1989, rising to 5% in 1997 and 8% in 2014 before topping out at 10% in 2019. “What does this have to do with gold investment? Well, when you purchase gold in Japan, you have to pay this tax, but you will get it back when you sell it as the tax should be borne by the person who consumes it,” he said. “In theory, this consumption tax should not have a negative effect on gold investment. Instead, it has its advantages, as you can now receive 10% over the selling price, regardless of whether you paid 0%, 3%, 5%, 8% or 10% tax when you bought it.”

Ikemizu said that the consumption tax did not work as designed, and instead had massive unintended consequences on the Japanese gold market. “In contrast to the tax treatment of gold in foreign countries, such as Hong Kong, where there is no value-added tax on gold purchases, bringing gold from Hong Kong to Japan without customs declaration and selling it here would allow you to add the consumption tax on top of the price, now at 10%,” he noted. “A 10% profit on gold incentivised extensive smuggling by both individuals and large-scale criminal organisations. Long liquidation of gold at the higher yen price and smuggling were the two primary reasons behind Japan’s gold exports, despite having only one small gold mine that produces just several tonnes annually.”

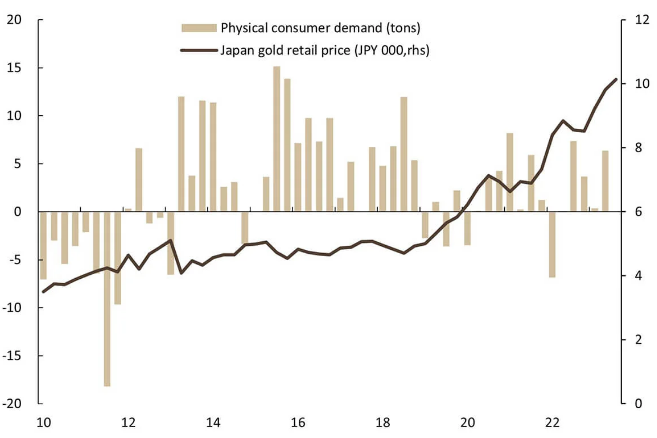

In the past, Ikemizu said the market would see “significant selling of gold bars and jewellery whenever the price jumped by 500 yen per gram,” and the opposite would occur when prices declined by a similar amount. “When I was trading on Tocom at a trading house many years ago, my simple yet consistently profitable trading strategy depended on Japanese investors’ tendency to hunt for bargains, as opposed to the Western investors’ trend-following style,” he said. “When London and New York sold gold, causing prices to drop, Japanese investors entered the market to snatch up bargains, and vice versa when investors in the West bought and prices rose.”

Japanese Gold Import and Export Balance (Source: UBS)

Japanese Gold Import and Export Balance (Source: UBS)

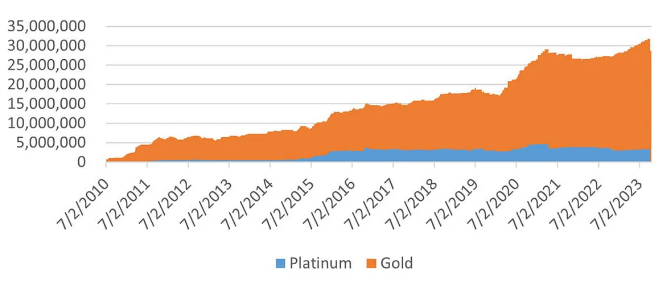

But Japanese investors’ bargain-hunting style has changed dramatically in recent years, and even record-high gold prices aren’t prompting them to sell. “For example, stronger prices had always attracted sellers at major retail shops, but nowadays, they report that sales and purchases are well balanced at their counters,” he said. “In the realm of gold ETFs, holdings in the US and Europe had been decreasing, but in stark contrast, Japanese gold ETFs is continuously increasing its holding despite the historically higher prices.”

Ikemizu pointed to three key reasons why Japan’s gold trade is now bucking its recent historical trend.

The first reason is an ongoing generational shift in investor attitudes. “Older generations were the primary buyers of gold in the 1980s and 1990s, and even until a few years ago,” he wrote. “However, now the older generation is exiting the scene, selling their gold, while a younger generation is entering the market. A decade ago, more than 90% of attendees at my investment seminar were older men and women. Especially after Covid, a much younger demographic, both men and women in their 20s and 30s, has become the majority.”

This new cohort of younger investors have never seen gold priced at 1,000 yen per gram. “Past price levels, which might have deterred older investors from investing at the current gold price, hold little meaning for the younger generation,” he said.

The second factor Ikemizu points to is the continuing depreciation of the Japanese yen. He noted that the yen began 2023 at 131 yen to the U.S. dollar, and it has since depreciated to 150:1, a devaluation of approximately 8.7%. “Combined with inflationary pressures, Japanese investors are increasingly concerned about holding yen in their bank accounts,” he said. “While the safety of bank deposits has traditionally been the preference of older generations, just holding bank deposits is no longer a safeguard against the depreciating value of yen. More investors are now viewing gold as a hedge against inflation and yen depreciation.”

Ikemizu said that gold investment in Japan has continued to rise even as prices have set new all-time highs. “This new investment purpose effectively explains the trend of Japanese buying gold despite historically high prices,” he said.

Gold retail demand is increasing despite sharply higher prices (Source: UBS)

The third key reason that explains Japan’s burgeoning interest in gold investment is the modification of the Nippon Investment Saving Account (NISA), which is based on the British ISA model, and was introduced in 2014. “Individuals who use NISA are exempt from paying the 20.315% tax on trading profits,” Ikemizu said. “This account, which has a limit of 1.2 million yen and a duration of 5 years, is set to end at the close of this year. The new NISA, which starts in 2024, will allow individuals to invest up to 18 million yen each, with no time limit. This reflects the government’s initiative to move funds from dormant bank deposits into investments.”

Ikemizu said that many people, including himself, never bothered to open NISA accounts because they considered the limits too small and the potential benefits negligible. “However, the new 18-million-yen limit with no time constraint changes the landscape entirely,” he said. “More and more investors are now opening current NISA accounts as they can have both the 1.2 million and the new 18 million, preparing for the expanded framework starting 4 January 2024.”

The new NISA program includes four gold, three platinum, two silver, one palladium and one precious metals basket fund. “In addition to physical gold products, we can naturally expect more investment funds to flow into precious metals from Japanese investors,” he said. “In fact, this trend is already underway with the Gold ETF, as most new investment in to it is coming from current NISA accounts.”

Ikemizu said he expects this trend to gain momentum in 2024 under the new NISA program’s significantly larger framework. “The Japanese gold market is undergoing a paradigm shift,” he concluded.

Japanese Gold ETF balance – continuously increasing despite higher prices (Source: Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking)

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and may not reflect those of Kitco Metals Inc. The author has made every effort to ensure accuracy of information provided; however, neither Kitco Metals Inc. nor the author can guarantee such accuracy. This article is strictly for informational purposes only. It is not a solicitation to make any exchange in commodities, securities or other financial instruments. Kitco Metals Inc. and the author of this article do not accept culpability for losses and/ or damages arising from the use of this publication.