When Nathan Silver sat down for an interview with Slant over a decade ago, Mackenzie Lukenbill noted that the director was “predominantly preoccupied with chaos.” The scope of his productions might have grown since then, but Silver’s core sensibility has stayed largely the same. His latest feature, Between the Temples, fulfills all the playfulness with both narrative and form on display in his early-career run of microbudget works.

The stars and scope might make Silver’s biggest production to date feel different than those before it, but the process to achieve his distinctive vision remains deeply collaborative. While Silver shares official screenwriting credit with C. Mason Wells on Between the Temples, the finer shadings of dialogue and character come about through workshopping their “scriptment” with their cast. Cameras roll before the actors have time to memorize their lines, lending scenes the paradoxical sensation of structured improvisation.

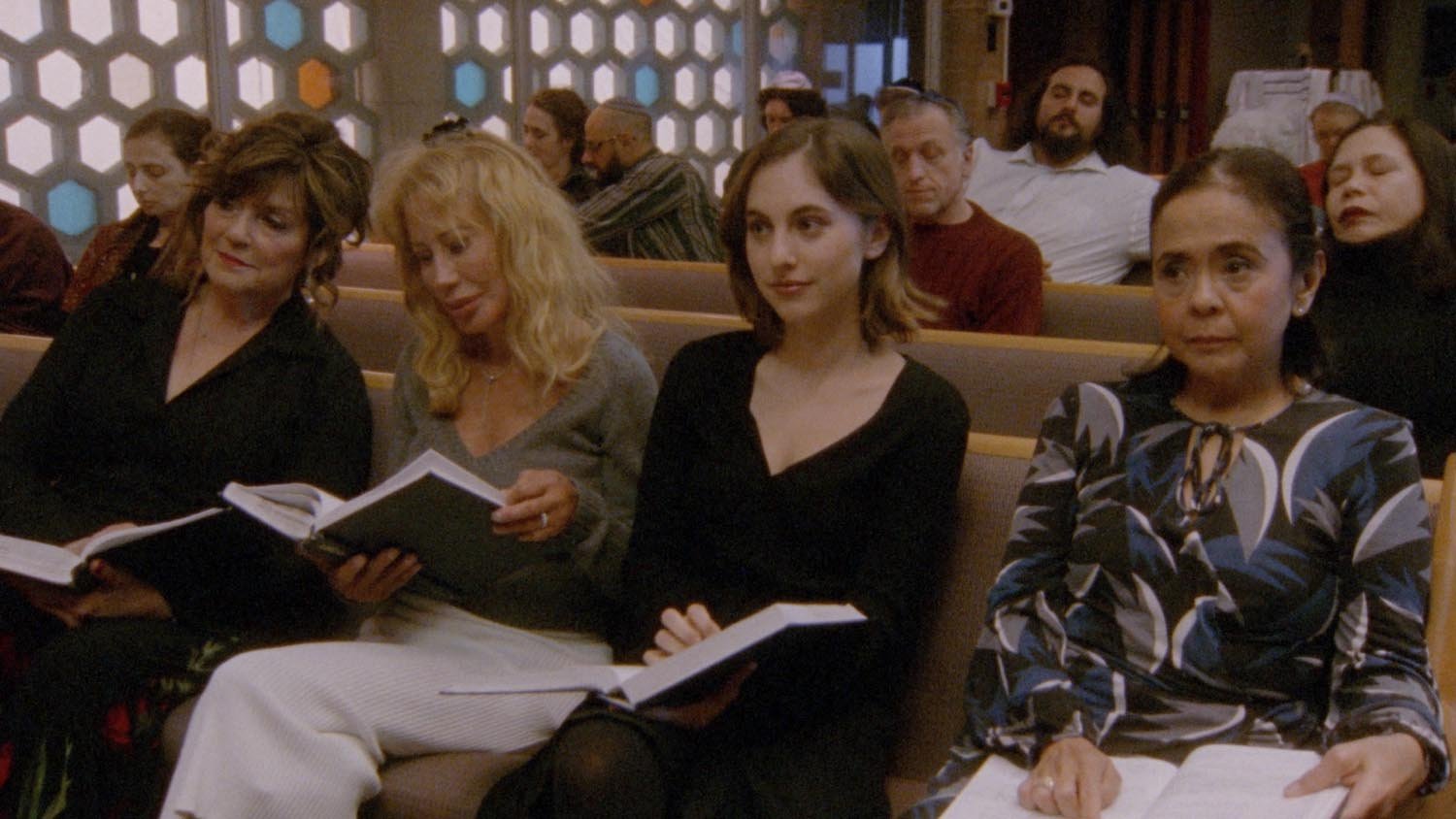

That style proves a perfect fit for the story of Between the Temples, a screwball-style comedy for the Shabbat-observant set. As an upstate New York cantor Ben Gottlieb (Jason Schwartzman) struggles to regain his voice literally and figuratively following the loss of his wife, he begins to find purpose again when reconnecting with his childhood music teacher, Carla (Carol Kane). Ben’s well-meaning but overbearing loved ones push him toward more traditional routes of reconnecting with romantic and professional satisfaction. However, only in preparing Carla for her unconventional late-in-life bat mitzvah does his life begin to make sense again.

The film resists forcing Ben and Carla’s relationship to fit into any familiar dynamics. At any point in Between the Temples, it feels like they could end up as friends or lovers, mentor-mentee or parent-child. That enticing sense of potential lurking within every scene seems directly correlated with the nature of the production itself, as Silver afforded his performers the latitude to explore the possibility within every scene while staying rooted in a strong sense of character.

I spoke with Silver, Cane, and Schwartzman ahead of the film’s theatrical release. Our talk covered how the collaborative writing process fleshed out the screenplay, what cinematographer Sean Price Williams’s reactive camerawork enabled on set, and where the actors saw parallels to some of their formative working experiences. But as we awaited Schwartzman to join the interview, some jocular crosstalk quickly gave way to profound discussion.

Nathan Silver: I was joking, they’re going to wheel Jason in here like Anthony Hopkins [in The Silence of the Lambs].

Back in the news!

Carol Kane: What do you mean?

NS: Trump keeps saying “the late, great Hannibal Lecter.”

CK: He does? Meaning what?

NS: Nobody knows!

CK: When does he reference that?

NS: At rallies, just like, “the late great Hannibal Lecter.”

CK: He says that apropos of what? In what context?

The most charitable explanation anyone has been able to provide is that they think he’s mixing up the political asylum process of immigrating into the country with mental asylums. Somehow, he makes the jump to Hannibal Lecter.

NS: Ah, yes. A surrealist gesture.

CK: Fuck me, motherfucker. What’s the thing where these people just follow him? My mother was so brilliant and alive during the time of the war with Hitler. As soon as [Trump] started campaigning for the presidency the first time, she saw him one time and said, “He’s Hitler.” She also said the first thing he would do is go after the press. It’s just extraordinary that it’s the same kind of insanity that people just seem to want to follow. I just don’t get that.

NS: It’s so excruciating to live in a time of complete idiocy and short-term memory. The past is close behind. The Holocaust is so close; it’s not even a century ago.

CK: I keep quoting the last line in The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, which I was privileged to do twice [at the Charles Playhouse in Boston in 1975] with Al Pacino, and John Cazale as the Goebbels character. I may be making one or two mistakes, but I think it’s: “Let’s not yet rejoice in his defeat, you men, the bitch that bore him is in heat again.”

NS: Oh my god! Yes.

CK: Doesn’t that just give you chills? He’s it again. Be on the alert for these people. [shudders]

I don’t know how we pivot toward anything lighthearted from this, but as someone who watches movies, I’m always attuned to questions posed in movies that doesn’t get answered. When Carla comes into Ben’s class, the one that gets interrupted is about what it means to be a good Jew. Do you all have any thoughts on it now?

NS: It means to question everything at all times. I think the foundation of Judaism is questioning, answering a question with a question. It’s not accepting the reality in front of you.

CK: So that implies profound thinking. Searching, right? Which is certainly not what’s happening nowadays.

NS: No. I think the primary concern is that we’ll stop asking questions out of laziness or exhaustion. I keep saying the Talmudic scholarship of living is Judaism. It’s just questioning everything.

CK: Raul Julia said this thing back in the day. He was talking about compassion fatigue. You get compassion fatigue, and then you move out of a real awareness that people need you. We were talking about children starving in underprivileged countries, and Raul said that the problem is people get compassion fatigue. I have to say, I’ve been guilty of that.

I think we all have. That gets to some of your questions about why people support Trump. The story they tell themselves is, “I’ve been waiting in line to get what’s mine, and these people come in and cut the line. How many people am I expected to have compassion for?”

CK: That’s really interesting.

How did you all choose Carla’s passage for the mitzvah? Leviticus isn’t exactly light reading.

NS: It came from our Jewish consultant, Jesse [Miller], who was also a co-producer on the movie…

CK: …and my Hebrew coach! A multifaced man.

NS: When he’s not working on movies, he tutors kids for their bar and bat mitzvahs.

CK: So, lucky me.

NS: It was kismet, though, because we were looking at when we were going to be shooting, and he said, “Well, what passage would that be?” And he said, “Oh, it’d probably be Kedoshim.” That just happened to be two of the producers’ Torah portions, too, Adam [Kersh] and Taylor [Hess]. Then, of course, it was both Carla’s and Ben’s.

What did the Mike Leigh-style collaborative process with the actors bring to the film that you and your co-writer couldn’t have imagined on your own?

NS: Well, because then you go out to the people who are actually going to embody these characters, and they come with their better brains. They have ideas and questions, and they poke holes in all the right places where it’s like, “These things are not quite thought out.” And they need to be because it’s going to be humans playing this. I want to get all of those better brains in a room and see what we can make together.

How has that process changed over time? As I was reading about some of your previous work, you used to not share the scriptment with the cast.

NS: I didn’t. I was foolish at the time, in some ways, because I think it’s much better for everyone to know the direction it’s going in. But also to have their input as to what direction it should go in, not the preconceived notion, and then to be open about that. [to Jason Schwartzman as he enters] You look like an ad for Starbucks.

CK: Nice to meet you. What do you do?

Jason Schwartzman: Hi, I’m Jason, I’m just here to take some photos of you guys.

CK: Can I get hair and makeup, please?

JS: I’ll just watch for now. [takes seat, leaving open space at table] Is it alright to sit like this?

NS: Elijah’s right here.

JS: [pauses] Elijah’s not here.

Jason and Carol, did either of your work with other comic luminaries at all inform the process of collaborating on the dialogue for Between the Temples, or was this process entirely its own?

CK: For me, I try and bring everybody that taught me if I have any brains in my head.

JS: Same for me. [But] Nathan has his own sense of what’s funny. That’s what I loved about his movies, and that’s why I wanted to be part of this. I want to be in his movie, so I want his input on how I can change or be different than I have been to service his thing. There are different movies, and everyone’s got a different vibe. Not that this means anything, but you know when you do something and someone’s saying, “Can you move the table this way?” You’re doing it like this [pantomimes moving the table in front of him], and then they’ll say, “Stop, that was perfect!” But you don’t know what you did that was perfect. You’re just like, “What?” And they’re like, “Do it again.” And you’re like, “I think it was like this?” That’s sort of like a lot of the creative process. Even if I’ve worked with people, I don’t necessarily know that I could recreate or bring something from one thing to another thing.

CK: That’s what’s so interesting. The core of it is some kind of insane trust that you all have to have, because you’re gonna all just jump off the bridge and hope that you learned in a way that other people can empathize with or understand! And you have to jump together. Our DP is jumping with us because he doesn’t know each take what the ultimate lines are or what the emotions will be because they’re changing. They’re based on this writing that’s extraordinary, but they’re also injected with the moment that the actors are sharing. The DP has to really snake around and be conscious and empathetic with what’s happening.

Does the visual language develop in tandem with the way that the script is being written?

NS: You go in with a preconceived idea, and then it’s destroyed on set because you’re reacting to what’s in front of you. Sean and I want to embrace the reality of the given situation rather than the imagination that isn’t on screen. He’s very much an actor. As both Carol and Jason have pointed out, he’s just in the scene acting with the actors. I call him “The Great Reactor.”

Does that change anything for you all as actors to know that the camera’s going to be more freewheeling rather than hitting specific angles or marks?

CK: Oh, it’s not that at all, that’s for sure! It really has to be in the moment. I’m just grateful for it because I love that he’s really finding what we’re finding at the same time. That’s an unusual gift, I think, for a DP. It reminds me of John Cassavetes and Al Ruban. That was so extraordinary, the way John used to get inside your heart and face. I think that these two gentlemen are not John; they’re themselves, but pretty great work.

Was there a guiding light or comic philosophy guiding the way? What grounded your exploration beyond the page to ensure that elusive “tone” stayed consistent?

NS: It was extremely structured. There’s a map for every scene. Maybe a couple in there are much more improv-heavy, but there’s the map there. Then, a lot of the jokes are written, and the characters are thought through. We had extensive conversations as to who these people are and what they would do in these given scenarios. You have that as the foundation of this, and then it’s not about hitting certain marks for like, “We need this for a punchline.” It’s about allowing the humor to come from the moment or the character and allowing the jokes to actually come from the person instead of from the writer.

CK: Harumph!

Between the Temples channels screwball comedies not just in the verbal wit but also in the physical comedy. Do you workshop that like the dialogue, or does it have to be discovered on the set?

NS: These two are a hoot together.

JS: Can I answer? It’s gonna be a weird, roundabout way, but it connects to the question about filming. The way that Nathan and Sean also preferred to work on this movie—I can’t speak for every movie—but I love the way this movie looks and feels. Unless I’m wrong, an effort was made to make the spaces workable at any given moment. In other words, there weren’t cables in one part of the room, so you were restricted to this area. So as much as you could say there was improvisation, it’s the movement and not the words.

CK: That’s really rare.

JS: There’s a scene in the movie where Carol tucks me into bed and she says, “I’m just gonna go downstairs if you need me.”

NS: I loved this.

JS: I believe in the script she’s meant to go downstairs. But instead, she just lays down on the ground. Three things happened there, I think. One is she had the impulse to do that. Two, Sean the great reactor was savvy, paying attention, and filmed it. Three, he was able to film it because Nathan had set up the room in a way where—

CK: We had the room.

JS: You had the room, so you could go anywhere at any time. The physicality, if anything, was allowed to be itself, because of the way that Nathan wanted to make the movie. It allowed for physicality and movement. Or like the scene where I go to the table, and Carol makes me do the breathing from my belly. That all kind of happened…

CK: My mother taught that belly breathing. I used her technique because, in fact, if it was real, that would really help Ben to connect.

JS: But that’s an example, it wasn’t in the script to get on the table. That’s Carol saying, “Get up on the table right now!” We’re improvising that, but that’s not just lines.

CK: And also him saying, “I’m gonna do this now” instead of “No, I would rather not!”

JS: So we’re doing it, and we’re able to go on the table. Next thing you know, we’re up there filming a scene. That’s atypical, I feel like, of most movies because a lot of people would say, “Well, I’m not lit for this.”

CK: That’s what they would say.

JS: “I’m not lit for him to go into the table. I’m not ready for him.”

CK: “It’ll take me another hour.”

JS: “That’s a separate setup of him on the thing.” But in this, that’s why Sean is like an actor too. It’s like an actor with a camera on their shoulder, and he’s just observing this happening. That’s a testament to the kind of movie Nathan makes and what was so wonderful about it.

NS: I’m grateful that my collaborators are willing to just give themselves to this process and way of working where you can’t really have an ego about any of this. It’s not like my co-writer Chris is like, “Oh, they didn’t say that line.” You can’t be precious about anything. You have to actually go with what’s happening. It’s about the moment at all times. They’re such lovely folks. Yeah.

How did you approach the sound design in the film? Beyond just the herculean task of mixing all the voices at the climactic dinner scene, there’s also all the clanging pipes at the synagogue, for one.

JS: I’m so happy that you’re just going into this zone because this is my favorite zone, so keep going.

NS: It starts off with that. I hate if production sound says we need to get the line clean. I’m like, “No, it’s fine. It’s dirty. People talk over each other.” You have some producers questioning, “How will this cut?” I’m like, “Trust me. I’ve done this nine times before. It always works in the edit.” And, of course, you get into the edit, and John [Magary, editor of Between the Temples] is obsessed with sound. In a dream world of his, he would just do sound design. He seems to love it the most. He would then start picking it apart and be like, “You didn’t get that line cleanly?” I’m like, “No.” Then he would figure out an alt take that he would slip in there that would fit the lips. He would make all these things work, and then he did so much layering. He came up with the sound of the door. He used some insane combination of dogs whining or barking.

I had a theory about what the door sound was…

CK: Let’s hear it!

It sounds exactly like the scream in the Skrillex song “Scary Monsters and Nice Sprites,” but maybe I’ve just seen Spring Breakers way too many times.

JS: I’ve got to check that out.

CK: That’s in Spring Breakers? [takes pen to write down the title of the film]

Yes, it’s the opening song that starts with EDM music, and then there’s a woman’s scream right before a bass drop that takes it into this crazy other zone.

NS: [laughing] I think John used a dog whelping. John was very fastidious about getting this chaotic, insane [feeling]. For the dinner scene, the number of tracks for that was a nightmare. Arjun [G. Sheth], my sound designer who I’ve worked with now for the last 15 years, goes in there and embraces it. He doesn’t try and clean it up. He tries to actually add more. I think you can watch the movie multiple times and hear new things each time you watch it because there are so many lines coming at you.

CK: But that door is such a prominent and bizarre character. It’s so there in a way that’s ridiculously powerful.

NS: Tim Heidecker called it “brave.”

JS: He prefaced it by saying he didn’t love the word “brave.” He goes, “I think it’s—well, I don’t like this word—but it was brave.”

JS: I think the way that the sound was recorded was [what was] so liberating about the scene. Because then it wasn’t broken apart. The scene is basically happening all at once, and the more typical way of doing it would have been to isolate each part of the table. “Everyone be quiet, now it’s our part of the conversation.” But what was great was we were all talking. It would have been different had I known that Dolly [De Leon], [who plays] my mother, could hear me talking to Carol. It would have felt different if the actors were quiet in the set and I had to say something just to her. There’s a safety, and that’s a wonderful thing. Because it was so loud and everyone was talking at the same time, we were able to say things to each other in private. It was a cloak.

I saw that you presented Between the Temples in a double bill with Rushmore over the weekend…

CK: Where?

JS: [deadpan] At my mom’s house. No, it was at the Aero Theater in Los Angeles.

CK: It was both the films together? How cool! And you were there?

JS: I went to the Q&A, yeah.

I couldn’t help but think about how each of your first leading roles in some way relates to the characters you play in Between the Temples—Jason playing a man trying to triangulate his feelings about a teacher in Rushmore, Carol playing a woman trying to understand what it means to be Jewish in Hester Street. Does the film feel full circle at all in allowing you to play through similar dilemmas with the benefit of decades more experience?

JS: I definitely didn’t even realize it until I saw them on the marquee. I thought, “Okay, there are some things that are similar here on the surface.” If anything, the thing that’s the most striking is both movies are kicked off by a loss. Max Fischer lost his mother, and Ben Gottlieb has lost his wife. You could say on the surface, “Wow, there’s this idea of a love triangle.” But the real connection that I saw was grief and trying to come back alive.

CK: I also didn’t think about it in a conscious way, although of course what I know about Judaism mostly comes from my research for Hester Street. In hindsight, I can see what you’re talking about. I think both characters of mine that you’re talking about are feeling extremely alone and isolated. In Hester Street, I barely recognize what my husband is meaning and up to. I want to be a part of it, but I’m not accepted. In this [movie], my husband and parents separated me from my hope and wish that I would get this bat mitzvah. And now this man gets me and wants me to do what I need to do, like the tenant in Hester Street who I eventually married.

And the film’s dedicated to [Hester Street director] Joan Micklin Silver, right?

NS: JMS!

CK: But I didn’t know that then!

NS: Her sense of humanist comedy—and Hester Street is not so much a comedy, obviously—was just key for me and Chris while we were working on the writing of it. We both adore her.

CK: If only she could have seen.

NS: And also the titles: Between the Temples, Between the Lines [Micklin Silver’s 1977 film].

CK: Oh yeah! I never made that connection.

Since 2001, we’ve brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.