Labour’s plans to use private finance to build infrastructure will cost taxpayers billions in extra repayment costs, experts have warned.

Sir Keir Starmer is planning to use private sector financing to boost Britain’s infrastructure, despite fears it may be more expensive than using public funding in the long run.

Industry insiders have warned such measures could lead to an expansion of toll roads and extra charges on customers’ bills.

Labour’s proposals bear similarities to Private Finance Initiative (PFI) contracts that were expanded under Tony Blair’s premiership and have cost taxpayers billions in inflated repayment costs.

Under PFI contracts, the private sector financed, built and operated infrastructure that was paid back over time by taxpayers.

The financing strategy was ditched by the Conservatives in 2018 after a number of NHS trusts required bailouts linked to the high cost of PFI schemes.

The National Audit Office, the spending watchdog, said in a 2018 report that taxpayers would pay £200bn to contractors over the next 25 years. Auditors found the cost of privately financing projects could be as much as 40 per cent higher than relying only on government money.

Under Starmer’s leadership, Labour has pledged to reduce risks for private investors and attract £3 of private investment for every £1 of public investment.

The party’s manifesto indicates private finance could be used to pay for roads, railways, reservoirs, energy sources and other “nationally significant” infrastructure.

Labour’s plans to attract private investment

Barry Gardner, head of climate change at Phoenix Group, an insurance company, told i some of the details of Labour’s pledges have not been fleshed out – but in principle mean the government take on a greater proportion of the risk in projects that are jointly funded with the private sector.

Phoenix, which is a member of Labour’s British Infrastructure Council – a group of firms independently advising the party on private sector investment – wants to invest billions in sustainable projects but has struggled to find options which would work for its investors.

Mr Gardner said Labour could use their £7.3bn “National Wealth Fund” to attract more private money for new technologies such as hydrogen production and carbon capture and storage, which may otherwise be viewed as “too risky”.

The Government could agree to cover losses for investors, for example. It already has guarantees in place for private investors in offshore wind farms, who are paid a minimum rate for the energy they produce. If the market rate is lower, the Government tops up their payments. If it is higher, the private firm gets to keep the excess.

Hannah Vickers, chief of staff at Mace, a consultancy and construction firm that will advise on a Labour-led review of major infrastructure projects, told i this type of model could work for gigafactories.

She said the risk for the Government is if it sets a minimum price that is too low, no firm will be interested. Too high and it could be expensive for taxpayers.

If technologies are inherently risky, such as small modular reactors, she said they “would command a premium from the private sector”.

A risk of taxpayer bailouts

Chris Thomas, head of the commission on public health and prosperity at the Institute for Public Policy Research think tank, said a problem with privately financing essential public infrastructure is that “the Government can never let them collapse”.

“We saw a lot of those involved in PFI taking fairly extravagant risks in terms of how their businesses operated, and we see this to an extent with social care now, which is a very private-finance dominated, private equity-dominated sector,” he told i.

“That leaves them able, in some years, to make very big profits, but it also means that you’re perennially at the risk of Carillion-style collapses unless you get the accountability and contracting absolutely spot on, which will take a massive expansion of government skill in doing that.”

The collapse of Carillion, a construction firm involved in delivered PFI projects, in 2018 cost taxpayers an estimated £148m.

Mr Thomas said one of the challenges of building essential public infrastructure with private finance is that the Government does not have the same level of contracts expertise as in the private sector. “We signed up to really bad deals,” he said.

Liz Emerson, chief executive of Intergenerational Foundation, said PFI contracts have left the public sector with a “mess” of “crumbling buildings” while private investors have made big profits.

“When the Government can borrow at much lower rates, why are we handing our national infrastructure over to the private sector who are delivering it badly?” she told i.

“The way the market works is that the investors want returns. If you’ve got massive pension funds who are investing in infrastructure and have to pay out to their beneficiaries, they are always going to be pressuring the organisations that they’re investing in for those returns.

“We have to find a new way of bringing the expertise, the engineers, the architects, the service delivery people in from the private sector without passing the costs unfairly on to younger and future generations. We fear that Labour are going to go back to PFI version one and two.”

Alex Chapman, senior economist at the New Economics Foundation, warned that “a lot has been tried and failed over the past two decades”.

“With Labour promoting heavily their ‘partnership’ with business, the public will rightly be concerned about a return to the failed model of the private finance initiative which saw private businesses invited to strip profit from public service investments,” he told i.

“If Labour is proposing a scale-up of public-private partnerships through vehicles like its National Wealth Fund they will need to be clear-sighted about what the public is getting back from the deal.

“Core public service infrastructure and natural monopolies should be off the table. Tight conditionality around public money should be the bare minimum. This means squeezing profit margins down in favour of good jobs, pay and environmental outcomes.”

Private finance ‘must be counted in public debt‘

Max Mosley, senior economist at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, said PFIs were widely adopted when Blair came to power because they allowed the Government to invest in infrastructure without the funding being counted in its public debt figures.

“They were able to effectively massively ramp up their infrastructure spending, and to all intents and purposes were actually spending less officially,” he told i.

Because deals were not counted as part of public debt, he said they were not properly scrutinised. Mr Mosley said many schools and hospitals were “signed up to PFI contracts that were way more expensive than would be normally allowed under normal procurement processes” and are now stuck with higher interest payments.

“Any large-scale infrastructure project that enables you to take that cost off your balance sheet is bad because it just leads to this situation where nobody’s watching you,” he warned. “There’s not enough accountability.”

Richard de Cani, leader of global cities, planning and design at consultancy Arup, which is also advising on Labour’s infrastructure review, said a “really important consideration” for Labour would be whether to set up private finance projects that would be counted as part of the Government’s debt.

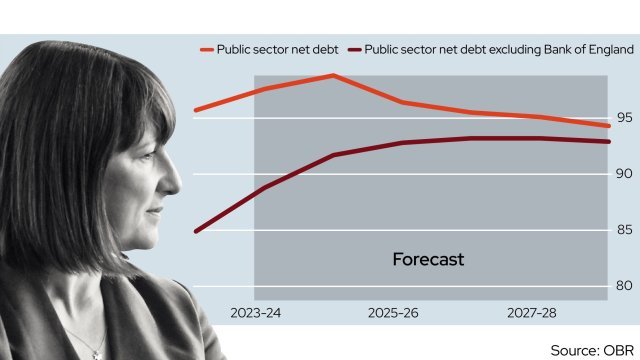

Labour has committed to keep the Conservatives’ economic targets that require debt to fall in the fifth year of official forecasts, which limits how much it would be able to borrow.

Mr de Cani said there have been some successful PFI projects, but they were typically counted towards the public debt and involved the public sector retaining control over key aspects such as fees and outcomes.

But if the projects are counted towards the public debt it “erodes” the benefits of using private finance to minimise government spending.

Mr De Cani said the next government will need to consider whether private finance projects will be good “value for money”.

“Often projects that are attracting private finance will cost you more over time,” he said. “But it’s a mechanism of enabling them to proceed at a quicker pace. So you realise the benefits earlier because you’re not dependent on public funding only, which is limited.”

He said sometimes people use the words “funding and finance interchangeably”.

“With finance, you need to pay it back,” he said. “And it’s often the mechanisms for paying it back that become the hardest to think about both in terms of their political acceptability, but also the certainty on those sources of revenue.”

He said it is “typically cheaper for the Government to borrow money than the private sector” but the limitation is the “Government’s willingness and ability to keep on borrowing”.

“If you, for example, look at a new railway line, and you’ve got the choice of building it in five years’ time with private finance, or waiting 15 years’ time for public funding, then the difference between the two is 10 years where the economic impact of that new railway line would not be felt so therefore you don’t get the wider economic benefits and everything that brings to the economy,” he said. “That’s often the argument that’s used. It’s about the ability to accelerate and bring forward.”

Toll roads and other ways of repaying private finance

Mr de Cani said a future government could pay back private investors by charging members of the public for using the infrastructure, or by charging public bodies.

He said toll roads are an example that is already being used in the transport sector.

The Silvertown Tunnel, a new road tunnel in London, has been privately financed and will be paid back via a toll on those using the road, as well as a toll on the existing Blackwall Tunnel nearby.

Transport for London will set these charges, which have an added objective of reducing traffic levels to improve air quality.

Mr de Cani said tolls on roads can be difficult to sell to the public, so aligning them with environmental goals can make them more appealing.

“The more that we can connect some of these different financing structures to other outcomes, particularly around the environment, the more successful and the more politically acceptable they will be,” he said.

Less publicly visible are payments made by public bodies for the ongoing use of privately financed infrastructure.

Mr de Cani said he worked on an extension to the Dockland Lights Railway that was a PFI project with a 30-year contract to design, build and maintain the railway.

Under the terms of the deal Transport for London (TfL) agreed to pay the company – a group of firms that came together to deliver the project – for the ability to operate its train on the railway. TfL retained control of fares charged to the public and the operation of the transport network.

“The public face of the railway is still TfL so it’s almost invisible,” Mr de Cani said. “It was just a mechanism for getting the railway built earlier.”

France and Spain has also used this financing method in transport projects. It is also being looked at as a way of privately financing a high-speed railway between Manchester and Birmingham to replace the northern leg of the HS2 project, which had been publicly funded but was cancelled.

Bill increases to pay off private finance

Another option involves building infrastructure that is privately owned but regulated by the public sector. Private owners can then charge customers to pay for it.

Ms Vickers said this can already be seen in airports and in the water industry.

Heathrow, for example, is privately owned and sets charges to invest in the airport. The fees are regulated to prevent the airport from charging whatever it wants because it is in a “monopoly situation”, Mr de Cari said.

Water companies are also privately owned and can add extra fees to customers’ bills to pay for long-term projects, which are overseen by the regulator Ofwat.

Thames Water, for instance, is using extra charges to pay for the Thames Tideway Tunnel, a large sewer.

“I can see challenges there,” she said. “If you take the water companies, for example, and how they’re regulated, there are some challenges there reputationally around attracting investment into those companies and those organisations when they’re seen to be failing from a regulatory point of view.”

Ms Vickers said there is “some discussion at the moment” around whether this strategy could work for nuclear energy projects, but she said the sector lacks an Ofwat-style regulator who could oversee this effectively.

She said fitting “the right models to the right deals in the right sectors” will be a challenge. “Some worked really well, some did not.”

Labour did not respond when approached for comment.

Election 2024

The general election campaign has finished and polling day has seen the Labour Party romp to an impressive win over Rishi Sunak‘s Tories.

Sir Keir Starmer and other party leaders have battled to win votes over six weeks, and i‘s election live blog covered every result as it happened. Tory big beasts from Penny Mordaunt to Grant Shapps saw big losses, while Jeremy Corbyn secured the win in Islington North.

Nigel Farage’s Reform UK also outdid expectations with four MPs elected.

But what happens next as Labour win? Follow the i‘s coverage of Starmer’s next moves as the new Prime Minister.