Oslo, with its neatly painted houses and serene waterfront, is not known for high drama. But in 2020, Norway’s capital erupted in controversy over one spectacularly wealthy investor, a splashy event in Philadelphia—and the biggest sovereign wealth fund on the planet.

That spring, Nicolai Tangen, the Norwegian founder of London hedge fund AKO Capital, was picked by Norway’s central bank to be the next CEO of its gargantuan oil-and-gas-financed investment fund, whose value had soared above $1 trillion. It soon emerged that months before his selection, Tangen had flown a private-planeload of guests to a gathering he had organized with his alma mater, the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. The event featured seminars, fancy dinners, and a $1 million performance by Sting—all at Tangen’s expense. The then CEO of the oil fund, Norway’s trade minister, and the country’s attorney general had all attended.

Such finance-nerd blowouts may be standard fare on Wall Street, but they were a jolt in discreet, low-key Norway. The news ignited a media frenzy and even a parliamentary inquiry over favoritism and conflicts of interest. Above all, the affair was at odds with the country’s squeaky-clean reputation—and with the perception of Norges Bank Investment Management, or NBIM, the fund’s asset manager, as a champion of better corporate governance.

“It got very messy,” says Anja Bakken Riise, executive director of Future in Our Hands, a Norwegian environmental NGO that fiercely opposed Tangen’s appointment. “He’s quite different from what we’ve seen in previous directors.”

When I visit Oslo—four years later—the brouhaha is still among the first things Norwegians mention when Tangen’s name comes up. But now it’s viewed more as a culture clash than a scandal (no formal allegations of wrongdoing were ever lodged). Inside NBIM’s sleekly modern headquarters, it seems to have largely faded from consciousness. Even so, the CEO remains “quite different” from Norway’s gray-suited bureaucratic class. He’s a voluble extrovert whose ease in the public eye is drawing renewed attention to the fund—now worth a stunning $1.7 trillion—and its potential to influence how companies behave.

“We don’t try to have influence because we want influence. We are trying to make more money in the long term.”

Nicolai Tangen

Tangen, who turns 58 in August, has begun the day with his year-round morning ritual: a 6 a.m. swim in Oslo’s ice-cold fjord, then a sauna at home and an electric-scooter ride to the office, where he plops his helmet on the coatrack and gets to work. Oslo is a world away from the London luxury of his hedge fund days. Yet he claims the moment he heard about the NBIM job, he badly wanted it. “I was like, ‘Wow, incredible, three things I love,’ ” Tangen says: “management, organizational development, and doing something great for the country.”

Tangen launched AKO in 2005 and built it into one of Europe’s biggest hedge funds; after NBIM hired him, he and his wife, Katya, placed their personal fortune of about $700 million into a charitable foundation. He describes his new, simpler life as idyllic. “You are close to the water, the ski slopes,” he says. “It is just fantastic.”

The relaxed style belies serious business. Founded in 1996, Norway’s oil fund now plays a key role in global finance—one starkly disproportionate to the tiny country of just 5 million people to whom the money belongs.

NBIM’s enormous holdings are equivalent to about 1.4% of the value of all public companies globally; in Europe, the fund’s share is closer to 2.6%. Its portfolio, which includes stakes in nearly 9,000 companies, is up about 60% in value since Tangen arrived in 2020; a live tracker shows the value changing by billions of Norwegian kroner per second during trading hours.

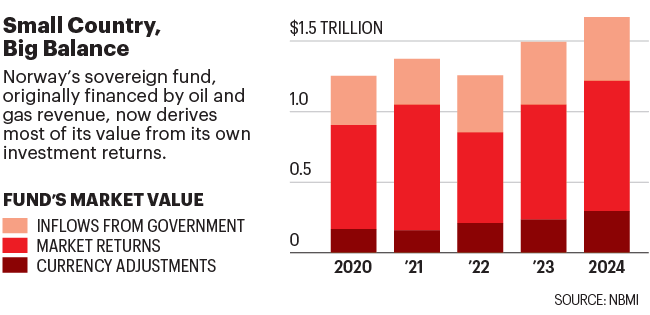

The shorthand “oil fund” is becoming a misnomer: While NBIM’s original assets came from Norway’s oil and gas revenues, only about one-third now do; the rest are derived from the fund’s market performance, according to Tangen. The fund also owns some of the world’s priciest real estate, from Manhattan to Paris’s Champs-Élysées, including about one-quarter of Regent Street, London’s stratospherically expensive commercial district.

Arithmetically, the fund adds up to about $300,000 for each Norwegian. Its ultimate purpose is to finance Norway’s social services, so that no citizen ever need worry about health care costs or retirement income. “It’s kind of like the national team in making money,” Tangen says.

The national team, ironically, is forbidden from investing directly in Norway itself, a restriction designed to prevent the economy from overheating. That marks a sharp difference from other sovereign entities, like Saudi Arabia’s $925 billion Public Investment Fund, which seeds homegrown industries like tourism and sports.

Instead, NBIM is constructed as a global index fund, with stakes in the world’s most influential companies. But Tangen—who holds graduate degrees in social psychology (earned in his thirties) and in art history (earned in his fifties)—has interests far beyond investing. In fact, his mind seems abuzz with almost anything but the nuts and bolts of financial returns. He’s engaging company—even before delving into his culinary passions (he’s a Cordon Bleu–trained chef) or his collection of about 5,000 Nordic artworks, for which he recently funded a museum in his hometown of Kristiansand.

Among Tangen’s current fascinations: what he believes is a uniquely Indian business attitude among CEOs like Microsoft’s Satya Nadella and Adobe’s Shantanu Narayen. “They talk about the importance of being in the here and now,” Tangen says. “Most people don’t talk like that.” Another: Norway’s decision to ban digital devices from schools, citing students’ distractedness. “It’s a fantastic decision,” says Tangen, even though NBIM owns billions in stock in Meta, Alphabet, and other attention-economy giants. “We’re not just talking about kids here,” he adds. “We’re talking about everybody. You cannot multitask the way you think you can.”

Tangen’s relentless curiosity was one motivation for launching a podcast, In Good Company, in 2022. The show features freewheeling interviews, 70 or so to date, with members of his ultra-elite circle, including Bill Gates, Sam Altman, and Elon Musk, who muse about leadership, business, and life. “Friendly, open-ended questions can get you pretty far,” he says.

Tangen believes the podcast has hugely boosted the fund’s profile, especially in the U.S.; he cites the roughly 1,500 résumés NBIM received for three summer internships in New York. When I ask what he has learned about leadership from his interviews, he says, “Empathy is the next big thing in management. It has been lacking for a while.”

Despite a track record of hedge fund success, Tangen has little opportunity to flex his investment skills in Oslo. The fund’s exceedingly cautious management style leaves almost no room for independent stock picks.

NBIM is overseen by the Finance Ministry, whose strict mandates dictate that the fund maintain a long-term-oriented, balanced portfolio with 70% equities and 30% bonds. Any adjustments to the mix require approval from Norway’s parliament, which has been deeply reluctant to grant them. “Every Norwegian knows Nicolai Tangen by name, but no more than a half-percent would know the name of the head of the asset management department of the Finance Ministry, who is probably 20 times more powerful,” says Sony Kapoor, an economist and former investment banker and an expert on sovereign wealth funds.

$1.7 trillion

Assets under management at NBIM, July 2024. Source: NBIM

The slow, steady approach has yielded about 6% average annual returns. That might be unsexy, but its predictability has won Norwegians’ trust, says Espen Henriksen, associate finance professor at BI Norwegian Business School. “It’s one of those rare instances where a public entity has [tapped into] the biggest financial trend of the past 20 years: the global index fund.”

Even so, some analysts believe NBIM could be doing far better. Kapoor argues that the fund should invest some of its money in private equity, and greater amounts in emerging markets like India and Brazil. Its conservatism “has long-term costs not only for the Norwegian economy,” he says. “At a time when the world desperately needs funding for the green transition, it is contributing almost nothing to it.”

Tangen argues that the fund can catalyze change in other ways. Its ethics council scrutinizes companies, and forbids investments in coal, tobacco or cannabis producers, companies that violate human rights, or those involved in nuclear weapons development.

NBIM also pushes for changes within companies—a longtime hallmark of the fund that Tangen has made more visible. It has backed a growing number of shareholder resolutions at annual meetings, especially on climate action and governance, which Tangen says directly impact the fund’s long-term returns. He estimates his staff holds 3,000 in-person meetings a year with company executives. Since Tangen became CEO, the fund has started publishing its voting decisions five days ahead of annual meetings, greatly amplifying its influence. Henriksen says NBIM has helped rally other shareholders to its causes: “The fund can push the needle a little bit in terms of better corporate governance.”

“The essence [of good leadership] is authenticity. You need to be who you are. Otherwise you have no credibility. People are not stupid—they look through you.”

Nicolai Tangen

Lately, it has been pushing harder. NBIM vehemently opposed a lawsuit that Exxon Mobil (of which it owns 1.23%) filed against climate-activist shareholders. And in June, two months after Musk appeared on Tangen’s podcast, it voted against Musk’s humongous, much-criticized pay package at Tesla, in which it holds a stake of about 1%.

A U.S. judge dismissed Exxon’s lawsuit. But despite Norway’s pressure, Musk won his compensation vote. Still, for Tangen, investor activism goes beyond short-term wins and losses: Socially responsible businesses are ultimately better investments, he says. “We don’t try to have influence because we want influence,” he notes. “We are trying to do all this in order to make more money in the long term.”

This article appears in the August/September issue of Fortune with the headline, “Norway’s Nicolai Tangen runs the world’s biggest sovereign fund. Can he leverage its assets to change business for the better?“