To some extent, the difficult fundraising environment of the past 18 months has propelled the adoption of gender-lens investment strategies in private equity. As LPs have gained negotiating leverage, they have been able to impose more requirements around gender globally – and Asia has some of the most catching up to do.

“In the last few years in Asia, we’ve seen LPs request, and some demand, more diversity on the boards of GPs – and this has been successful. Side letters for ESG [environment, social, and governance] requests have been a hot topic for the last 4-5 years, but in the past 18 months, specific diversity requests have become more explicit,” said Ann Ng, a Hong Kong-based partner at law firm Maples Group.

“Historically, it was just the pension plans and endowments that made these types of requests, but now we’re starting to see other institutions such as insurance companies, banks and larger family offices make them as well.”

This activity is not limited to first-time funds or small funds. Indeed, the larger the ticket size, the more GPs have proven willing to agree to special new terms in this vein. In addition to demanding female representation on GP boards, some side letters have also pressed for managers to engage an in-house DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) officer.

Still, the impact of the downturn on the uptake of gender-lens investing depends greatly on how strictly one defines the term.

Selling diversity

The advantages of having a gender-diverse team are well established in industry research, with a 2019 study by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and Oliver Wyman being the most widely cited evidence. It found gender-balanced funds achieved 20% higher returns on average versus male or female-dominant funds.

Investors can point to similar statistics in support of gender-bias deployment strategies, reasoning that more diverse portfolio companies will outperform. But gender-lens investing in this sense is not necessarily benefiting from LPs’ increasing capacity to influence managers.

On one side, the overall universe of gender-lens funds appears to be expanding. In a report published last April, 2X Global, an organisation that promotes gender-lens investing, identified 126 gender-lens managers globally, acknowledging that the count was not exhaustive.

The survey, which was conducted alongside Visa Foundation and climate and gender-lens advisory Sagana, estimated assets under management in gender-lens funds now amount to USD 7.9bn, up 400% since 2017.

Most of these GPs are Fund I’s that did not exist a few years ago; many are still fundraising. They have made some kind of codified commitment to incorporate a gender lens in their operations, although they do not necessarily invest only in women-led or women’s-empowerment businesses. A majority target Asia but only a smattering is based in the region.

Their proliferation is attributed to the mainstreaming of gender-lens strategies across a wider range of GPs and LPs amidst a broader lift in appetite for impact and ESG qualifications.

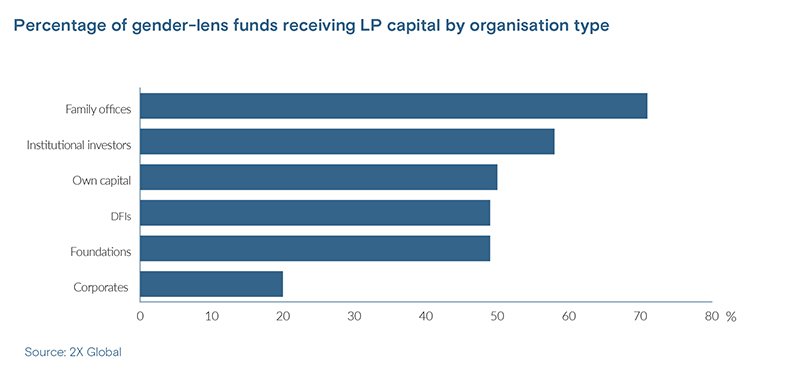

Almost 50% have received investment from either a development finance institution (DFI), a foundation, or both, while 58% have attracted other types of institutional LPs, according to 2X. The caveat is that generalist impact funds with a gender-lens overlay are getting the attention, while their pure-play gender-lens counterparts are not.

“LPs are quite happy if there’s a gender lens that’s added to a conventional private equity strategy, but when we see more innovative types of structure or a first-time team – even if they have amazing track records from before they came together – that’s still really tough to fundraise,” said Jessica Espinoza, CEO of 2X.

“That’s where DFIs, family offices, and foundations could play a much more catalytic role.”

Pioneer spirit

The lack of track records for pure-play gender-lens managers appears to remain a significant inhibitor, even for ostensibly catalytic capital providers. AVCJ Research has no records of a Fund II in this strategy in Asia. Most of the few that exist globally are based in the US with global mandates.

Asia-based managers seeking encouragement may turn to Nigeria, where Aruwa Capital, which invests exclusively in women-led businesses in sub-Saharan Africa, is currently targeting USD 40m for its second fund. One LP, a global foundation, said the process was “going really well.”

The standout pure-play in Asia is Singapore-based Sweef Capital, which spun out from US impact private equity firm SEAF in 2021 and closed its debut fund last December on about USD 45m.

Sweef came in well below its target of USD 100m, which was set before the spinout in 2018. But there is a sense in-house that if the fund didn’t have its gender-lens differentiator, it would have raised even less.

The five-year process allowed plenty of time for Sweef to build a reputation for being persistent, passionate, and one of the only namechecked options amongst the few institutional investors seeking exposure to a pure gender-lens strategy. Eventually LPs started cold calling.

The fund is anchored by PBU, a Danish public pension fund, and features the likes of Paypal, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and Australian Development Investments (ADI), a government programme. There are also 15 family offices, mostly representing Western markets and including Australia’s Tattarang.

“While I’d anticipated that our fund would end up being mostly backed by DFIs, that didn’t happen in practice,” said Jennifer Buckley, Sweef’s founder.

“What did happen over that time period is that the private sector, starting from behind, has really moved ahead in this area and become much more progressive and thoughtful, mostly for commercial and organisational reasons. Our type of fund fits the strategic objectives of those LPs.”

Change agents

ADI, a DFI-style programme launched by Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, hints at how the universe of institutional investors with gender-lens agendas and appetite for unproven managers could expand.

ADI has been capitalised with AUD 250m (USD 168m) for a mandate comprising two core themes: climate-tech and gender-lens. It is managed by Canada-headquartered Sarona Asset Management and invests primarily in funds across Asia Pacific.

Linda Mok, a Singapore-based director of investments at Sarona, said the fund will be largely guided by 2X criteria, which has emerged as a de-facto standard for establishing gender-lens credentials. It will also invest in funds with aspirations to achieve that status.

One Vietnam-based manager, for example, is under review for a potential LP commitment. Mok described the firm’s first fund as commercially successful and coincidentally invested 60% in women-led businesses. The idea is for ADI to help the GP establish a systematic gender-lens approach for Fund II.

“We do expect funds to get to 60%-80% 2X alignment across the portfolio by the end of the fund life. The funds can invest in sector agnostic companies that are not women-founded, but we expect them to put in place that post-investment value-add,” Mok said.

“We don’t just want to seed funds and companies that are already excellent but to really help them and support them on that growth trajectory.”

Broader efforts in this vein include IFC and British International Investment (BII) publishing their Fund Manager’s Guide to Gender-Smart Investing in 2020. Its recommendations span deal origination and portfolio management, advising managers to begin by first promoting in-house diversity.

BII, a founding member of 2X, previously put this direction into practice by taking an active role in developing a gender strategy for Singapore-based Insitor Partners, a women-led impact investor focused on low-income communities in South and Southeast Asia.

The support included incorporating gender considerations into investment strategy and tracking the impact of portfolio companies by separately analysing data for men and women.

“Many funds apply gender considerations as an intersectional lens alongside climate resilience and-or serving underserved and low-income households,” said Kate Perkins, interim head of gender and diversity finance at BII.

“Historically, we have evaluated the strength of the GLI [gender-lens investing] framework and the centrality of gender to the impact thesis of the fund when we invest in fund managers.”

Wider adoption?

It is hoped that the characterisation of gender-lens investment as more about transformation stories and finding a nexus with climate will widen the range of manager types that adopt the strategy, as well as bring more scale to the concept.

A USD 500m investment by Temasek Holdings in LeapFrog Investments last year – touted as the largest-ever commitment to an impact investor – has been interpreted as an attempt to blend social and gender-lens elements into the sovereign investor’s otherwise climate-focused ESG agenda.

LeapFrog, which focuses on financial technology and healthcare in emerging markets, received 2X certification for its latest flagship fund, which closed on USD 135m in 2022 with support from Temasek and IFC amongst others.

Currently, the phenomenon is firmly rooted in venture capital. About 60% of gender-lens managers identified by 2X globally deploy in VC, versus 30% in growth-stage PE and only 6% in buyouts. This is usually attributed to the idea that most women-led businesses, especially in Asia, are at the start-up or early-growth stages.

Leadership in buyouts is most often ascribed to EQT, which engaged Jen Braswell, founder of 2X and formerly head of value creation at BII, as head of impact in 2022. The firm’s key gender-lens investment initiatives to date have revolved around improving in-house and portfolio-level diversity.

It remains a pertinent question, however, why no large mainstream private equity firm has yet launched a pure-play gender-lens fund with or without women investors leading the strategy.

In theory this could be achieved in the same fashion as climate-dedicated funds launched in recent years. A manager with a large generalist portfolio compiles its past deals that incidentally support the climate thesis, thus establishing a track record to substantiate a specialised fund.

“I wouldn’t say the lack of interest in pursuing gender-lens funds is entirely driven by the difficult fundraising environment. A lot is also driven by whether or not people really believe that investing in women-led funds or businesses is an attractive risk-return strategy,” said one fund-of-funds investor.

“On the GP side, we have this talent bottleneck of very few women in senior investment positions, so that brings the question back to the men. How many truly believe in and know how to invest behind female talent for the future?”

Trouble at the top

The concern around this talent bottleneck is that women in private equity are often forced to choose between starting a family and career advancement at a time when they’re transitioning from junior to senior roles. This effect has been mooted as another reason gender-lens funds are more prominent in venture versus private equity.

Women in VC are more likely to have operational backgrounds in industries that are less vulnerable to the mid-career attrition seen in finance. They therefore join fund managers, starting in senior investment roles where, according to research by IFC, they invest in almost twice as many women-led businesses as their male counterparts.

Underrepresentation of women in senior investment roles could also impede uptake of gender-lens strategies at the LP level. This complicates the prospect of male-led gender-lens funds validating the strategy as the gender balance in GP leadership slowly corrects.

“We have one fund where the partners are all men, but 70%-80% of the employees in the underlying portfolio companies are women, CEOs and senior management, so it’s disproportionately impactful,” said a second fund-of-funds investor.

“You could take something like that to LPs to see if it meets their gender requirements, but it becomes hard because everyone has their own ideas about what gender investing means. This part of the industry is still fairly nascent, so there’s a whole cascading chain in terms of LP expectations.”

All of this is mounting pressure on managers to diversify their leadership, a trend perhaps best captured by the legal and advisory service providers helping them do it.

Ng of Maples, for example, said that at least three newly launched GPs in the past 18 months have come to her asking how they can bring women onto the board, although she noted these were proactive measures rather than responses to specific LP demands.

“We do a lot of consulting and advisory work for PE and VC firms to integrate a gender lens or to become 2X qualified. We are typically paid by the DFIs that are invested in them to do that, but more and more, we’re getting commercial PE funds asking us to do it and paying directly,” said Raya Papp, co-founder of Sagana. “We just finished one of those in Africa.”

This is an encouraging development, especially in the context of a fundraising environment that has prompted side letters demanding more diverse investment teams.

Please be patient

Wariness of LPs imposing this kind of quantitative standard on GPs is based on the idea that gender balancing must be a gradual process to ensure all hires are properly qualified. So, if managers are pre-emptively seeking women for leadership roles rather than scrambling to satisfy LP demands, it reduces that risk.

As LPs leverage their negotiating position to nudge GPs toward gender-lens strategies, they will do well to remember that the shifting of mindsets and cultures is generational work. Even seemingly flick-of-the-pen workplace policy reforms may need an extended timeframe to fully realise their benefits.

“It has to be a tactical influence on the culture at GPs, how they create an inclusive and flexible environment that doesn’t compromise on productivity. That’s difficult to argue against, but I still don’t think you can be too prescriptive about it,” said Brooke Zhou, a partner at LGT Capital Partners.

“For example, most GPs’ maternity policies seem pretty decent on paper, but there can still be a lot of pressure on women taking maternity leave depending on the culture of the firm. That culture varies widely and can’t be changed with a side letter.”