This March, the Biden-Harris Administration released another strategy to decarbonize the transportation sector: the National Zero-Emission Freight Corridor Strategy’s goal is to set the stage for fully zero-emission trucking by 2040. However, as 2024 is a historic election year, this new roadmap is challenged by reports, like the one from Roland Berger consulting firm, claiming this plan would need a trillion dollars from taxpayers’ money.

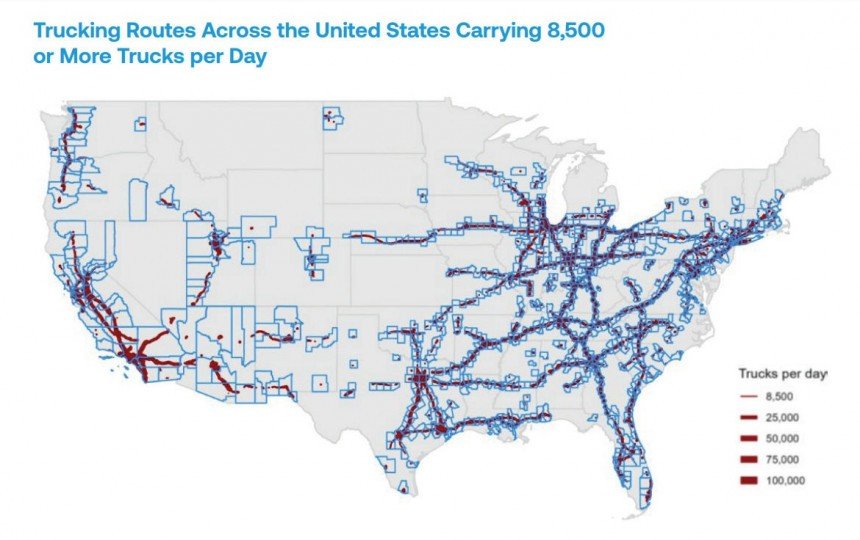

You don’t have to be a professional economist to conclude that this sum needed to ensure full US commercial truck fleet electrification is HUGE. The largest fleet of any other country in the world, totaling nearly 30 million registered trucks, consequently needs an immense recharging infrastructure.

“A massive investment gap”

This is what the Clean Freight Coalition asserts regarding the most recent report from Roland Berger: “Forecasting a Realistic Electricity Infrastructure Buildout for Medium- & Heavy-Duty Battery Electric Vehicles.” A report released shortly after the Biden-Harris Administration’s ambitious strategy.

This new plan aims to accelerate the sales of ZE-MHDV (Zero-Emission Medium- & Heavy-Duty Vehicles): at least 30% of total new sales by 2030 and 100% by 2040. Well, the transportation stakeholders across the trucking and motorcoach industries seem to consider these goals too high-aimed for their capabilities.

The Roland Berger report suggests that “fleets and charge point operators will need to invest $620 billion into charging infrastructure,” while “utilities would need to invest around $370 billion on distribution grid upgrades and new builds.”

According to Roland Berger Senior Partner Dr. Wilfried Aulbur, the US road freight industry has a yearly turnover of about $800 billion and a profit margin of around 5%. It cannot invest the hundreds of billions required by the study findings “without financial support or a significant increase in freight rates.”

If you read between the lines, the gentleman simply says this infrastructure needs taxpayers’ money, one way or another, either by huge governmental subsidies or by increasing prices of goods. This sounds like a convenient bullet for the other you-know-who presidential candidate, but let’s not dive into politics for now.

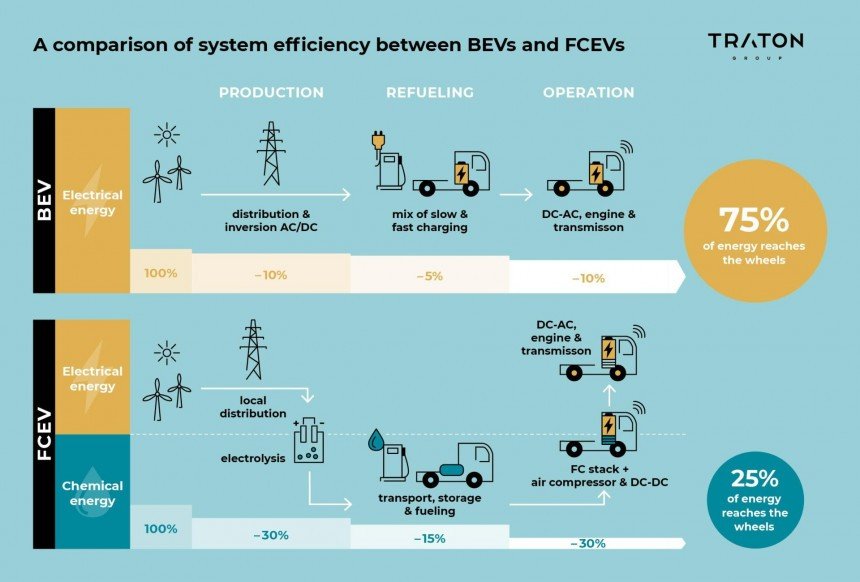

Still, I can’t help noticing another remark: “Electrification […] requires an openness to alternative technology paths to decarbonizing the heavy-duty segment.” If this means hydrogen, it’s ok, as the infrastructure strategy includes H2 trucks. But if this means e-fuels and other ICE-based solutions, frankly, this is a fishy statement.

By the way, almost all these vehicles use diesel engines, and their high pollution level harms more than 72 million people in the US. According to the American Lung Association, they are predominantly Black, Brown, and low-income communities living near port and freight infrastructure.

You may know these neighborhoods as “diesel death zones,” as a New York Times opinion by a climate advocacy group representative bluntly exposed an inconvenient truth. Of course, conspiracy-loving trumpists could accuse Sleepy Joe of trying to gain millions of votes by this ZE-MHDV infrastructure strategy – but I already told you I wouldn’t turn this into a political debate.

What’s this NZE Freight Corridor Strategy all about, anyway?

According to the Evergreen Action climate change advocacy group, which presumably contributed significantly to the Inflation Reduction Act, this new governmental plan is the “largest-ever coordinated investment in cleaning up the freight supply chain.” I’m trying not to be biased here, so I’ll call it just a logical strategy, although I admit it’s pretty bold for these times.

The most interesting thing is that it’s a four-part plan that will unfold over the next 16 years. So, you should get rid of that nasty idea that Roland Berger’s report most probably instilled in you that those hundreds of billions are needed like right now.

Those $620 billion investments exposed by the report translate into an average of less than $40 billion per year. That’s roughly 5% of the freight industry’s yearly turnover, the same report claimed. But most likely, this money will come from governmental funds and private companies investments – those who much better understand such a plan, I may add.

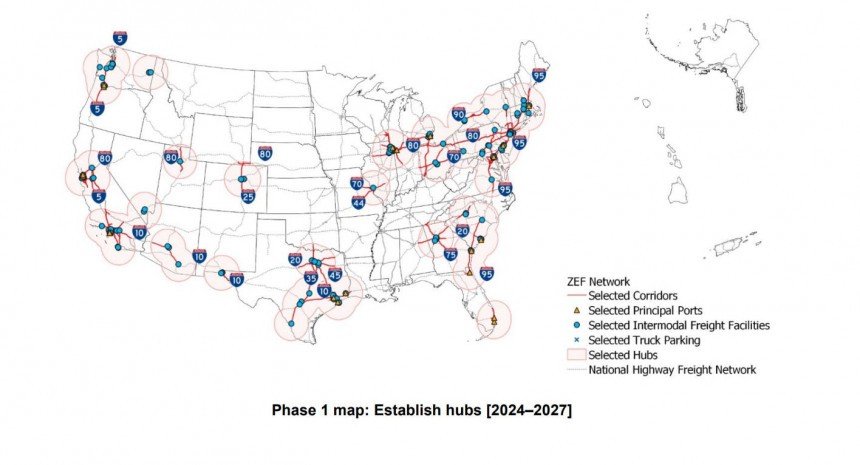

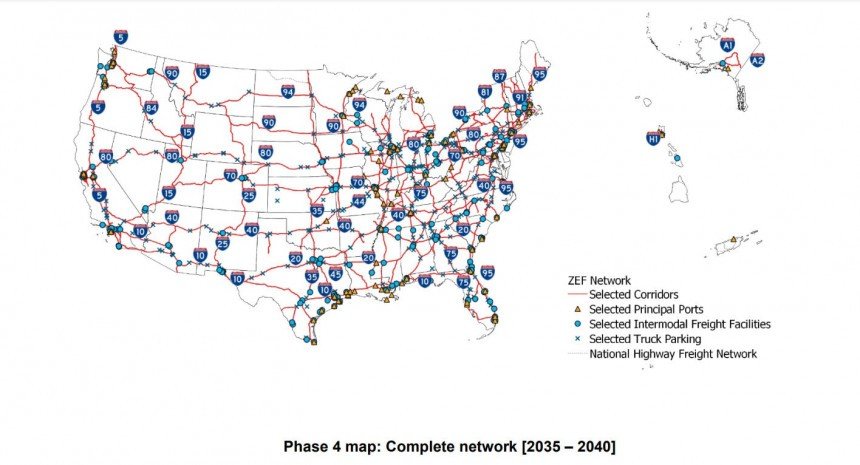

In the first phase, between 2024 and 2027, the plan aims to establish key freight hubs within a 100-mile radius. Think about these hubs as super-sized parking lots with more than a few megawatt-charging stations, and then add some megawatt-scale power energy facilities. The kind you often hear utilities complaining about that is undoable.

As a matter of fact, the Roland Berger report shows that utilities should invest in these facilities nearly the equivalent of “what was invested into the entire distribution grid over the past 15 years.” I remind you that those around $370 billion stated by the report are needed over the next 16 years. Frankly, is there any real issue here?

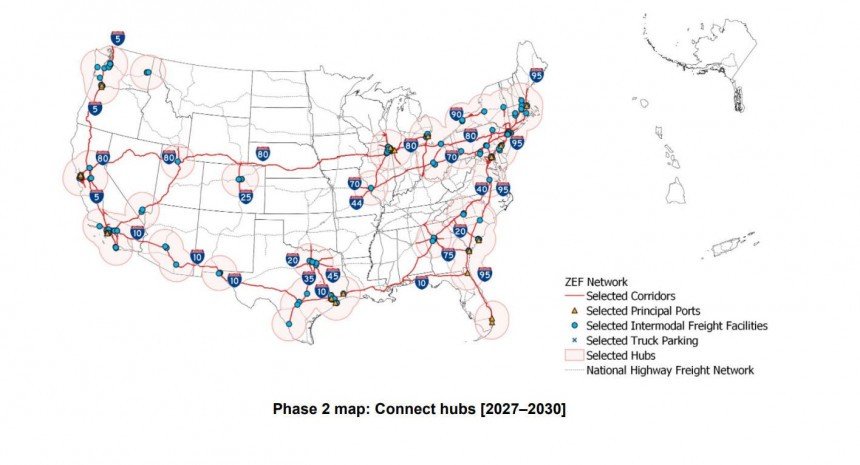

In the second phase, between 2027 and 2030, those hubs will be connected along critical freight corridors, accounting for roughly 25% of the final corridor network. The plan will prioritize the most disadvantaged communities and consider the states that have adopted California’s Advanced Clean Truck rule.

At the end of this decade, if all goes well, there will be 19,000 miles of Zero-Emission Freight corridors, concentrated in the most important areas. The East-West “electric connection” will still be scarce, as only two major routes are projected in 2030.

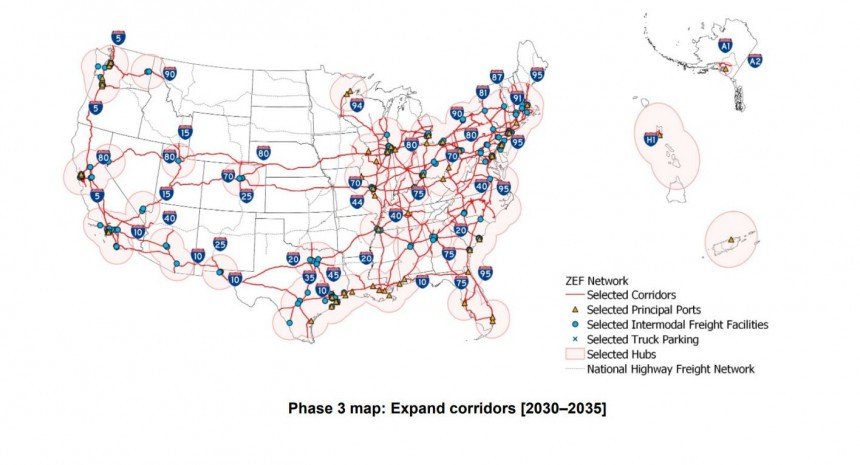

Between 2030 and 2035, in the third phase, the number of hubs and connections between them will expand. It’s interesting to note the expectations for the spreading of hydrogen fuel cell truck technology and the hydrogen refueling infrastructure along freight corridors.

Finally, between 2035 and 2040, the density of ZEF corridors should be more than enough to meet the needs of zero-emission goods transportation all over America. These corridors are expected to be nearly 50,000 miles long, while the ZEF hubs’ total surface will be more than 3 million square miles.

Is this infrastructure worth $1 trillion?

The American Lung Association’s own report on the impact of ZE-MHDVs states that, by 2050, the public health benefits due to cleaner air could amount to more than $700 million, thanks to around 66.000 fewer premature deaths, 1.75 fewer asthma attacks, and 8.5 billion fewer lost workdays.

So, health benefits will offset three-quarters of the one trillion investments. Then, such an ambitious strategy is expected to create millions of jobs, translating into billions of dollars worth of taxes.

Lastly, while electric trucks are more expensive than their diesel counterparts, their running costs are several times lower. While the Roland Berger’s report emphasizes a difference of two to three times between the price of a regular Class 8 diesel truck and a similar battery-electric one, this is more of a worst-case scenario example.

In real life, there are more and more examples of electric heavy-duty vehicles offsetting the price gap thanks to more favorable running costs, combining the advantages of the much lower price of electricity and the taxation of diesel truck emissions.

It all comes down to the TCO (Total Cost of Ownership) for the freight industry. Also, IDTechEx expects the electrification of medium- & heavy trucks to be accelerated by the adoption of the Megawatt Charging standard, which will overcome the major obstacle of charging times.

If you ask me, there’s another factor to keep in mind: by 2040, diesel prices will only go higher, while electricity sourced mainly from renewables will be cheaper by the day. Batteries will be more and more affordable, while their performance will exponentially improve. Hopefully, hydrogen technology will catch up. But you know what? Hydrogen infrastructure is also very expensive.

According to Emmanouil Kakaras, the vice president of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, the US and Europe need to invest at least $1 trillion for transitioning from the current fossil fuels infrastructure to a hydrogen-based one. Europe has already committed to $750 billion in investments, despite the recent Saudi Aramco CEO’s comment that ditching fossil fuels is a “fantasy.”

In the end, I can’t help but bring politics into context. If you-know-who will become again the President of the United States, I bet this strategy for the infrastructure needed to spur road freight electrification will burn in flames. Will those one trillion dollars be better spent?

I think not. According to a last year BloombergNEF report, the G-20 member states, including the US, of course, provided $1.3 trillion of support for the fossil fuels industry. Also, according to the International Energy Agency, global energy investments in fossil fuels were around $1.05 trillion, 50 billion more than in 2022. So much with those COP climate summits, huh?

There’s another angle to consider the $1 billion needed for the ZE-MHDV infrastructure: it’s less than 5% of the more than $21 trillion required for the global electricity grid to become net-zero by 2050. Upgrading the grid is no longer debatable, so it’s only logical to invest in charging hubs and ZEF corridors. Even if it seems too costly.