The 2024 Budget Speech revealed that Sri Lanka intends to accelerate Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) to secure the required investments and expertise to facilitate continued provision of much needed public infrastructure projects across the country. PPPs are widely understood to be a collaboration between the government and private sector to share responsibilities, risks, resources, and expertise, aiming to deliver services efficiently and generate significant returns whilst reducing the burden on public finances (The World Bank’s Public Private Partnership Monitor).

Against the backdrop of Sri Lanka’s efforts to come out of its current economic crisis, which was largely caused by the mismanagement of public finances and unsustainable levels of national debt – partly taken to fund large scale public infrastructure projects, this indication to involve the private sector in public infrastructure service provision going forward is a positive and sustainable sign.

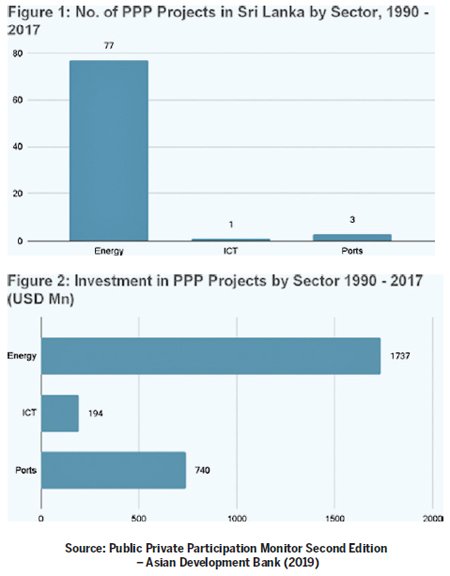

PPPs are not a new approach to securing investments in public infrastructure projects in Sri Lanka. In fact, from 1990 to 2017, the country entered into 81 PPP infrastructure projects worth $2,671 million, primarily in the energy, ports, and ICT sectors. The well-known South Asia Gateways Terminals (SAGT) at the Port of Colombo, which began in 1999 is a successful example of a PPP in Sri Lanka. However, the PPP framework in Sri Lanka at present is characterised by multiple institutional and regulatory weaknesses, which should be resolved before PPPs can fully serve to facilitate sustainable infrastructure investments in the country.

Regulatory Weaknesses

For starters, there is weak compliance with the existing project prioritisation framework (i.e., the Public Investment Programme or PIP prepared by the Department of National Planning) in deciding which public infrastructure projects, including PPPs are to be implemented in Sri Lanka. It is precisely this that has allowed for different administrations over the years to pursue infrastructure projects without regard for policy priorities and based on political considerations which have often resulted in low returns and a high burden on public finances (e.g., Mattala International Airport). However, once the new Public Finance Management Bill is approved, going forward, there will be a legal requirement to comply with the PIP for all infrastructure projects proposed through public investments or PPPs.

There is also no clear legal framework for PPPs in Sri Lanka at present. Currently, there is no specific law for PPPs and the  existing guidelines from 1998 have failed to address crucial issues pertaining to land rights, foreign investor participation, environmental and social issues, dispute resolution, and enforcement mechanisms. Instead, guidance for these issues is found in various other acts and regulations. It is also silent on State Owned Enterprise involvement in PPP projects. However a new PPP law is reportedly in development to address these issues.

existing guidelines from 1998 have failed to address crucial issues pertaining to land rights, foreign investor participation, environmental and social issues, dispute resolution, and enforcement mechanisms. Instead, guidance for these issues is found in various other acts and regulations. It is also silent on State Owned Enterprise involvement in PPP projects. However a new PPP law is reportedly in development to address these issues.

There is also no clear central authority to implement and oversee PPP projects in the country. The World Bank supported the establishment of the National Agency for Public Private Partnerships (NAPPP) in 2017, recognising the need for a central authority to define the country’s PPP pipeline and provide guidance to line ministries and other agencies on project selection, procurement, contract management, and more. However, the NAPPP was shut down in 2020 before implementing much needed reforms to the 1998 guidelines, leading to fragmented decision-making across line ministries, the cabinet, and the NAPPP.

Institutional Weaknesses

The NAPPP was reestablished in 2022, however stakeholders have revealed that it still lacks the technical expertise and capacity to function effectively and currently functions in the capacity of an advisory board. In addition, there is a lack of technical expertise even at the line Ministry level, who are responsible for implementing PPP projects. As an example, stakeholders have revealed how PPPs are often misunderstood as ‘free gifts’, when in reality private investors expect payment, either through user fees or government payments over the contract duration.

A lack of technical expertise in public entities, coupled with the fact that there is currently no requirement to conduct pre-feasibility studies to determine if infrastructure projects should be pursued with public or private funds, has resulted in PPPs being implemented without regard for fiscal risks and a reliance on private investors’ viability assessments. This has fostered an environment where PPPs are procured and implemented with little transparency, impacting institutional credibility and investor confidence. These effects are exacerbated in the case of unsolicited proposals, which account for a majority of PPP projects today.

The way forward

While addressing all PPP regulatory and institutional weaknesses is critical, it is equally important to implement reforms at the right political moment. The political climate can significantly influence the feasibility and success of these reforms. Keeping this in mind, reforms should focus on the following areas:

Legal and regulatory reforms: Accelerate the enactment of the new PPP law, which should improve transparency, mandate competitive bidding, and require reports on financial and technical feasibility studies by the NAPPP and relevant ministries before implementing PPPs. The NAPPP should be given legal authority, and the roles of line ministries should be clearly defined in their engagement with PPPs. The Public Investment Program (PIP) should be published online, and there should be a legal requirement to comply with the pipeline.

Capacity building: The NAPPP should be legally empowered and have the budgetary provisions to recruit skilled personnel in project financing, engineering, finance, banking, and law, as well as to access multilateral development grants. Additionally, line ministries should be empowered to establish PPP units and recruit these skilled professionals.

Improving the investment environment for PPPs: PPPs should initially focus on transferring existing government assets for private operation and management. Once debt restructuring is complete and investor confidence improves, PPPs can be pursued for new projects. Additionally, implementing tariff exemptions on selected construction materials and providing guarantees against expropriation can enhance the investment environment.

Yasmin Raji and Nirmali Ameresekere