(Bloomberg) — The glitzy Victoria Square development, boasting two skyscrapers and a new Hilton Hotel, was to be a new landmark for the London commuter town of Woking. Instead, it stands as a monument to how financial bets by local councils can go badly wrong.

Most Read from Bloomberg

The hotel is yet to open its doors. Work to replace unsafe cladding on the outside of the building, which dominates the skyline of the town of 100,000 people, will only be completed this summer, almost four years after the complex’s scheduled opening was blown off track by the Covid-19 pandemic. The original budget for the development has more than quadrupled to more than £700 million.

A combination of cuts in funding from central government, higher interest rates, Covid and, and above all, soured bets on commercial real estate are set to leave Woking Borough Council with borrowings of £2.4 billion, compared with its net budget of £24 million.

It became the first of three councils last year to issue a so-called Section 114 Notice (in effect, a declaration of bankruptcy) after winning the unwanted title of England’s most indebted council relative to its population. Now it is being forced to slash spending on key services.

“The council lived beyond its means,” said Ann-Marie Barker, the Liberal Democrat leader of the council who replaced her Conservative predecessor in 2022. “We’re moving to be a smaller council.”

It isn’t alone. Birmingham, Britain’s second-biggest city, and Nottingham in the East Midlands are set to reveal their cost-cutting plans after issuing their own Section 114 Notices in recent months. According to the Local Government Association, which lobbies for almost all UK councils, one in five of its members say they are very or fairly likely to follow by the end of next year, something that would force them to cut many of the services they provide to millions of Britons. In all, England’s local councils have £95 billion of loans outstanding for investment projects.

Many blame the policy of austerity that began under the Conservative-led coalition in 2010 for the hollowing out of local government finances: as grants from central government were cut, local councils were given greater powers to borrow money. Since then, Woking council’s funding from Westminster has fallen by about 69% in real terms, according to the National Audit Office.

“Ultimately, the funding and resilience has been sucked out of our public services and pre-election what we’re hearing is ‘there is no money’,” said Jack Shaw, an affiliate researcher at the Bennett Institute for Public Policy at the University of Cambridge.

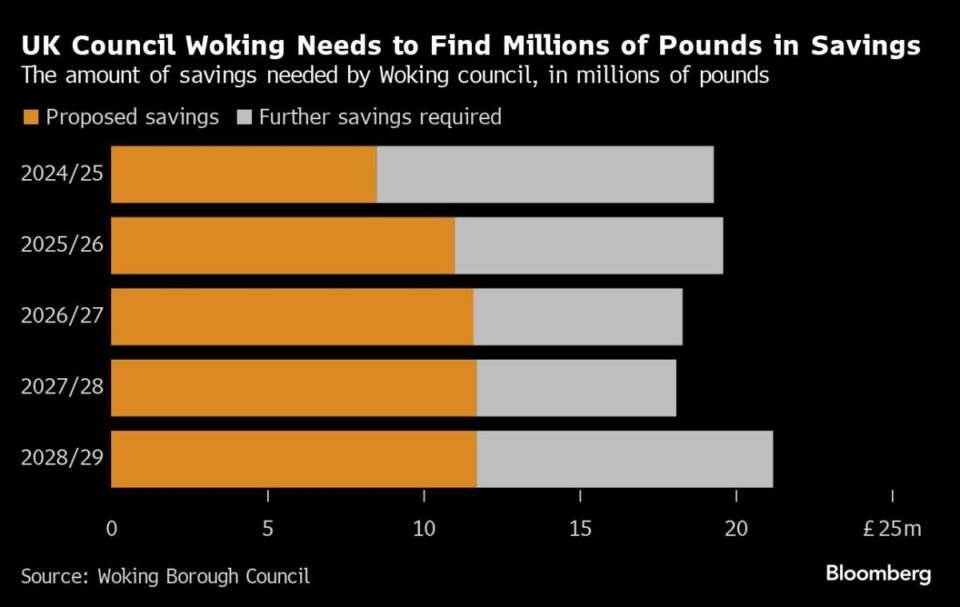

Next month, the council in Woking will vote on a package of cuts aimed at saving about £12 million annually. The town’s residents face the closure of their public swimming pool and council-owned public toilets while funding for sports pitches and the town’s main art gallery is being removed.

For people like Brian Truman, the cuts could be devastating. The 90-year-old widow is a familiar face at St. Mary’s community center on the outskirts of Woking where, five days a week, he turns up for lunch and company.

In coming months, the council’s funding for the center will go, meaning its services, which range from bingo to hot baths, will move to premises several miles away and a £20-a-day charge will be introduced. It’s a move Truman and other locals dread.

“It saves my life coming in here,” he said in an interview. “It’s fantastic, it does so much for me.”

As spending cuts begin to impinge on services that were previously untouchable, who gets the political blame could play a crucial role in an election year. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s Conservative Party held the parliamentary seat of Woking with a near-10,000 majority at the last election. The party led the council there until 2022, when the Liberal Democrats took over.

James Johnson, co-founder of pollster JL Partners, points to the role local politics played in the last general election in 2019. According to him, many voters in Labour’s traditional heartlands turned to the Conservatives for the first time in part because they were angry with what they saw as years of the party’s mismanagement of their local councils.

“The issues of national leadership, the economy, and immigration will be the biggest factors at the general election — but it is not inconceivable we could see the same effect now happen in reverse where Tory councils have let their voters down,” he said.

For Labour, the financial troubles of local government could turn into a headache if the party gains power as current polls suggest. Leader Keir Starmer has blamed “short-term inadequate funding” by the government for the crisis and has pledged to overhaul council budgets — but the party is yet to outline any detailed plans and has promised to take a prudent approach to spending overall.

The crisis has prompted calls for an overhaul of how councils are funded, with some urging the government to grant local leaders more fiscal autonomy.

“We as a country have the least money allocated at a regional or a local level of any in Europe,” said Barker. “We need to move away from that.”

English local authorities have less fiscal autonomy than other countries with federal systems, such as the US. There, states have a much wider range of revenue raising options and get a bigger share of the tax take. In Britain, councils rely on central government grants for about half of their funding. The rest comes from a form of residential property tax and a levy on business premises — but local councils have only limited control over these. They must share business rates with central government, and increases in council tax are capped each year.

Successive governments have shied away from any radical overhaul of local government finance since the introduction of the poll tax in 1990 triggered riots and helped to bring down then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. As a result, the rate of property tax residents pay still depends largely on the value of their house more than 30 years ago.

Under the Conservative-led coalition government of 2010-15, councils were granted more flexibility to borrow for investment in capital projects. Using cheap loans provided by the Public Works Loan Board, part of the Treasury, many councils pumped money into shopping centers and office blocks in the hope of generating income that would help to finance local services.

For many, including Woking, those investments have turned into liabilities as Covid hit and the real estate market turned.

The costs of the Victoria Square project ballooned from an initial £150 million to £460 million when the project was approved in 2016, only to soar to as much as £700 million, according to a government-commissioned review of Woking’s finances in May. As well as Victoria Square, the council also embarked on a £500 million plan to redevelop a whole residential district in 2017. Together, the two real estate projects account for the majority of Woking’s borrowings — and the cost of servicing that debt has ballooned to £62 million annually.

“The scale of borrowing was disproportionate to the council’s assets and ability to manage complex commercial activity,” the government inspectors said in their report. “There was insufficient regard to the level of risk the council was being exposed to.”

For Woking’s residents, the ramifications of the debt crisis are becoming clear. At St. Mary’s, locals of all ages are rushing to come up with ideas to keep the services running and have launched a petition. Jonny Moles, who runs the center, said in an interview the council’s plans are “devastating” and will “kill what we do” by removing the services for the elderly and hampering the running of its cafe.

“It’s purely financial, this decision,” he says. “What we’re trying to say is there’s more to it than that.”

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.