Because many consumer brands have been around for 100 years or more, it is easy to assume that they are immortal, churning out cash for their owners through thick and thin. But this is not the case. We are all prone to survivorship bias: the human tendency to forget what has disappeared from view. Brands that are eclipsed by something better, or disappear due to regulation or people’s changing preferences, may linger as a nostalgic memory, but their phenomenal success is forgotten.

How do you define a brand? A popular definition is a product, service or concept that is distinguished from competitors in the minds of consumers by its name, qualities and reputation. This implies that it can command a premium price. Many businesses, such as shops, airlines and cars, achieve brand recognition but struggle on that last test or, as in the case of petrol stations, fail completely.

Companies spend huge amounts of money trying to create new brands, but once the initial marketing blitz ends, sales often drop off. The new brand may stagger on for a while, but it then dies. Successful brands require long-term advertising and marketing support that is carefully pitched to sustain the price point, innovation in packaging and an understanding of the changing preferences of customers.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don’t miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don’t miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The recent problems at Diageo and LMVH show that it is easy to overestimate brands’ pricing power. The willingness of customers to pay up for premium drinks labels has faded, yet cutting prices may devalue the brand. Drinkers have other priorities for spending money amid the post-Covid squeeze on their wallets. No doubt these brands will recover, but some that were once huge never have.

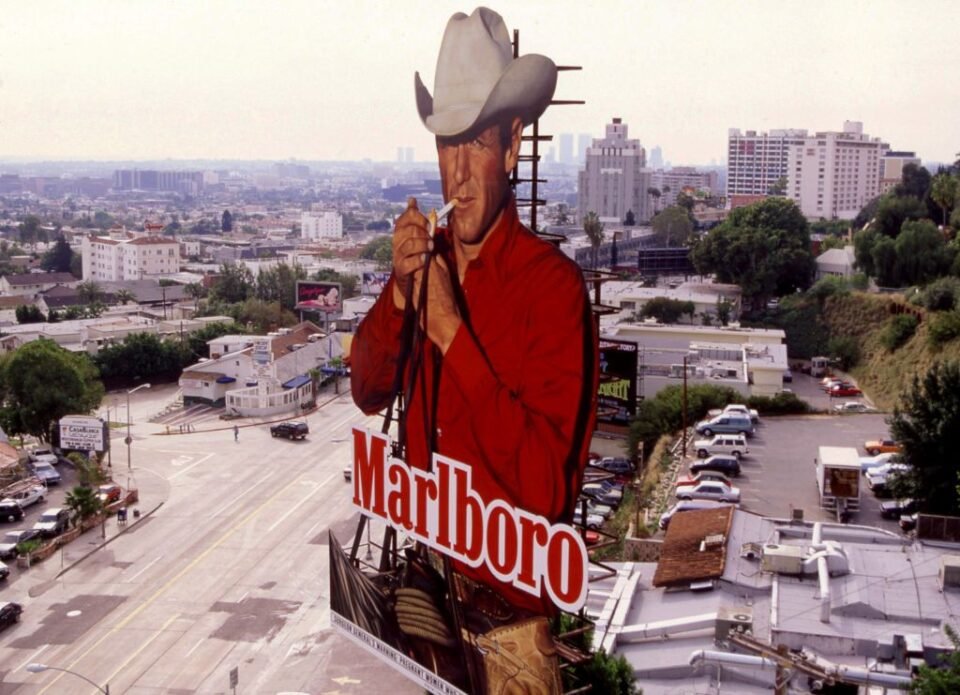

The death of Marlboro Man

Marlboro was the most famous of the many cigarette brands, which were killed off as advertising, sports sponsorship and other forms of marketing were banned by governments around the world.

The Marlboro brand was created by Philip Morris in the 1920s as a woman’s cigarette but was repositioned in the 1950s using the image of the “Marlboro Man”, a cowboy complete with a Texan hat. This gave a rugged, outdoors male image while the addition of a filter to the cigarettes, once regarded as effeminate, was supposed to make cigarettes safer to smoke.

Supported by heavy advertising, sales quadrupled in two years and Marlboro quickly became the world’s most popular cigarette. Other cigarette companies resorted to undermining it by seeking a ban on its advertising. The death from lung cancer of a succession of actors who had featured as the face of the “Marlboro Man” did nothing for the brand’s image. Marlboro still sells 240 billion units a year and is the top-selling cigarette worldwide, but the value of sales has fallen by a third since 2015, and the latest country to ban its advertising was Indonesia in 2012.

Bye-bye Babycham

Bambi’s favourite tipple, Babycham, is a sparkling perry developed by drinks company Showerings in the early 1950s. Initially, sales were disappointing but when its price was quadrupled to four shillings a bottle, they took off.

It was marketed as a “Champagne perry” (pear cider) with a trademark “Bambi” deer and was the first alcoholic drink to be marketed on television. Its appeal was as a sophisticated brand for young women to drink in the pub. Their mums drank port and lemon, or Guinness.

Sales peaked in the 1970s at 144 million bottles a year. In 1978, the Champagne houses sued to stop the use of their trade name. Although they were unsuccessful, Babycham stopped calling itself a Champagne. Sales declined and attempts to revive it were only temporarily successful as its target market switched to wine and other cheaper alternatives. Showerings floated on the stockmarket in 1960 and was bought by Allied Lyons in 1968, but the Showering family bought the brand back in 2021 from an intermediate owner. Let’s see how successful they are.

Blackberry: The first smartphone

Mobile phones first appeared in the 1980s as large, clunky brick-like devices, but the phones soon got smaller and their battery lives increased. Nokia came to dominate the European market with its handy pocket-sized phones, but fiddly texting was the only service other than the capacity to make phone calls.

The first BlackBerry smartphone appeared in the late 1990s and took the market by storm, being able to send and receive emails. It worked on several different wireless networks, offered security and used its own servers. Before Wi-Fi became widely available, at a time when bandwidth was also in short supply, customers enjoyed the ability to read messages and delete emails without downloading the text. Companies liked the control it gave them over corporate usage.

At its peak in 2011, BlackBerry had 85 million users. But then Android and Apple arrived, which cut the ground from under BlackBerry’s feet as they offered better technology, while mobile networks were also developing rapidly. By 2016, BlackBerry was down to 21 million users. Some traders still reminisce nostalgically about their BlackBerries, but none would swap their iPhones for one now. The lesson for investors is that brands have tremendous longevity if carefully nurtured, but they do not necessarily last forever.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek’s magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.